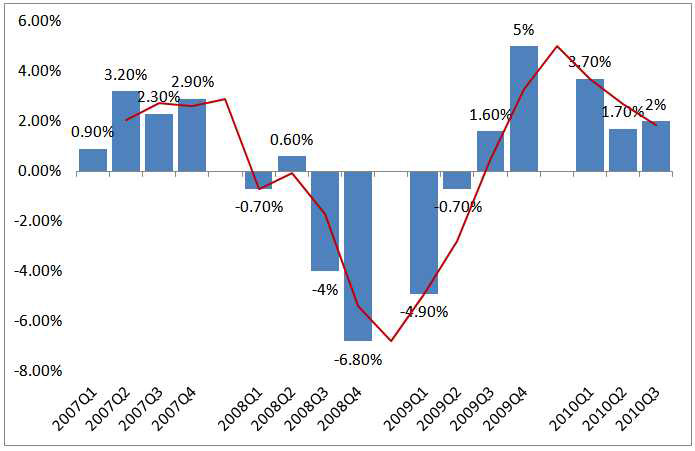

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the third quarter came in at 2%, a slight increase from the prior quarter of 1.7%. The increase is attributable to accelerated spending by the consumers and business investments in equipments. Although the economy is moving in the right direction, the pace is too slow to ignite employment.

In September, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) officially declared that the Great Recession was over in June 2009. Since then the U.S. economy has benefited from a very powerful inventory rebuilding cycle, culminating in the 4th quarter of 2009, along with the fiscal and monetary expansion. This combination stabilized the general economy. In fact, during the first quarter of this year, there was talk of raising interest rates by the middle or end of this year and beginning to shrink the Federal Reserve balance sheet. However, during the second quarter, the domestic economy began to show signs of weakness and the drumbeat of a double-dip recession grew louder. Government programs, from cash-for-clunker to the first time home buyer credit and the Public-Private Investment Program which intended to stimulate the private sector, have all come to an end. The evidence thus far suggests that a successful handoff from the public sector to the private sector remains uncertain and illusive. Although most economists and market observers feel there is a low probability that the U.S. will experience another recession soon, there is almost no disagreement that the domestic economy is expected to continue to experience very slow growth for the next few quarters and that this economy’s recovery will remain protracted with unemployment being the biggest drag.

To support and stimulate the economy, the government has two sets of tools – fiscal and monetary. Fiscal policy means adjusting taxes or public spending up or down to either propel or restrain total spending. After the creation of the unpopular TARP program to save the financial system and with 2010 being an election year, politicians have no appetite for an expansionary fiscal policy. Regardless of the final composition of the House and the Senate after next week’s elections, new public spending is a non-starter. That leaves the entire burden on the shoulder of the Federal Reserve which controls the nation’s monetary policy. Under normal economic cycles, the Federal Reserve changes the short-term interest rates to either grow or slow down the economy. With short-term rates at 0%, the Federal Reserve can only rely on unconventional means to stimulate the economy.

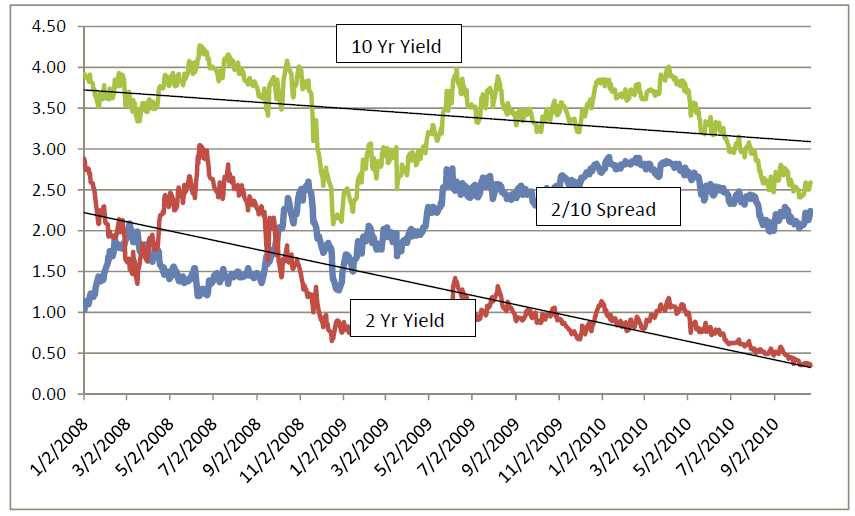

One such method is the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet (i.e. printing money) through a process known as Quantitative Easing (QE). QE is to expand the money supply through a process known as the open market operations. In essence, the Federal Reserve purchases financial assets, such as mortgages, government bonds and corporate bonds from banks and other financial institutions. This injects cash into banks and other financial institutions which creates excess reserves and, in theory, promotes lending and ultimately stimulates the economy. By massively soaking up bonds held by these institutions, bond prices would increase as interest rates fall. This kind of open market operation allows the Federal Reserve to target specific segments of the bond market as well as the yield curve in hopes of realizing its intended objectives. In the depth of the Great Recession, the first QE was put into action and the Federal Reserve balance sheet grew from US$870bn in August 2007 to US$2.2trn today. However, much of the cash injected into the banking system remains with the banks in an effort to repair their own balance sheets and is added to their capital reserve during a period where the economy remains uncertain for consumers and institutions. Furthermore, loan demands remain tepid during a period of deleveraging and credit repair.

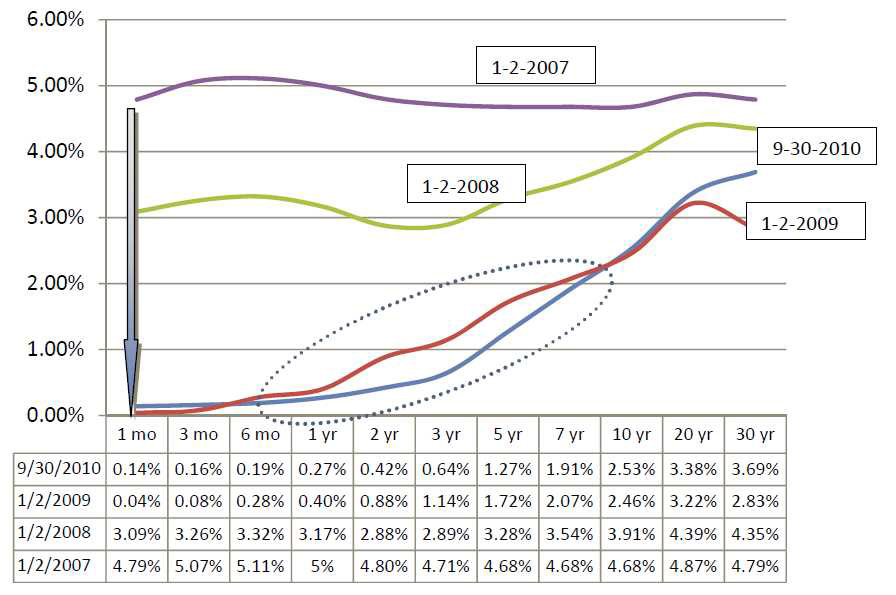

At of the end of the third quarter, the total return for the BarCap U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (the most widely used gauge to measure the performance of a basket of investment grade U.S. fixed income securities) was 7.94%, and for year to date, as of October 29, the total return was 8.33% while the yield is 0.23% for 1 year Treasury and 2.69% for 10 year Treasury. Most of the year to date return disparity has been price appreciation. To illustrate the movement of the yield curve over time, the following table shows the historical bond yields at the beginning of 2007, 2008, 2009 and as of the end of the third quarter this year.

Since January 2, 2009, the 3 year Treasury has dropped its yield from 1.14% to 0.64%, a 44% reduction. This reduction is a result of the first QE and the market responding to supply and demand. The 10 year Treasury had dropped 2.77% from January 2007 to the end of the third quarter this year.

With the unemployment rate stubbornly remaining around 10% and the fear of deflation, the Federal Reserve is again expected to act. During the August 27, 2010 Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Chairman Ben Bernanke said that:

“the FOMC will do all that it can to ensure continuation of the economic recovery. Consistent with our mandate, the Federal Reserve is committed to promoting growth in employment and reducing resource slack more generally. Because a further significant weakening in the economic outlook would likely be associated with further disinflation, in the current environment there is little or no potential conflict between the goals of supporting growth and employment and of maintaining price stability.” He concluded by saying, “The Federal Reserve is already supporting the economic recovery by maintaining an extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy, using multiple tools. Should further action prove necessary, policy options are available to provide additional stimulus. Any deployment of these options requires a careful comparison of benefit and cost. However, the Committee will certainly use its tools as needed to maintain price stability–avoiding excessive inflation or further disinflation–and to promote the continuation of the economic recovery.”

This is the first official hint that a second QE (QEII) is on the table. Then again on October 15, 2010, during the Revisiting Monetary Policy in a Low-Inflation Environment Conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the chairman stated

“[g]iven the Committee’s objectives, there would appear–all else being equal–to be a case for further action … a means of providing additional monetary stimulus, if warranted, would be to expand the Federal Reserve’s holdings of longer-term securities. Empirical evidence suggests that our previous program of securities purchases was successful in bringing down longer-term interest rates and thereby supporting the economic recovery.”

The market is treating QEII as a foregone conclusion, and it is now a matter of the amount of QEII. The Federal Reserve watchers are divided into the “shock and awe” group, where the Federal Reserve’s actions next Tuesday are expected to be huge, and the more contained and gradual alternative. There is no consensus as to the overall effect of a new round of monetary expansion. The benefit will most likely be psychological and affirms that the Federal Reserve will take every action required to save the economy and to prevent it from a Japan style multi-decade deflation. Many are fearful of a further expansion of the Federal Reserve balance sheet. If not monitored and managed properly this could lead to significant inflation in the future. One thing is for certain, QEII will mean the dollar will devalue further making U.S. made goods and services cheaper, and this will put pressure on the central bankers of other developed economies to also take action to mitigate the risk of anti-competitiveness.

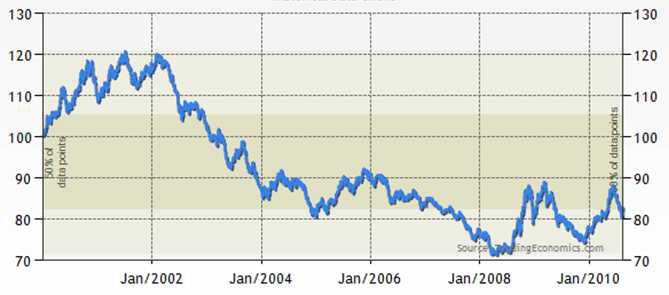

The U.S. dollar has been under pressure as a consequence since Chairman Bernanke’s August comments. During the 30 years starting at 1971, the U.S. dollar index (DXY) reached a historical high of 164.72 in February of 1985 and a record low of 71.33 in April of 2008. The US Dollar Index is a leading benchmark for the international value of the US dollar measuring its performance against a basket of currencies which includes: EUR, JPY, GBP, CAD, CHF and SEK.

With QEII, the dollar is expected to continue its fall against other major currencies. As the graph below shows the general trend is that, as the 10 Year Treasury interest rate declines, so does the US dollar.

This continuing deterioration of the US dollar is creating trade and political tension globally. On September 27, the Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega stated that “We’re in the midst of an international currency war”. The currencies of the developing nations (primarily the U.S., Europe and UK) have been depreciating since the financial crisis heated up. With consumer deleveraging, austerity programs and extreme monetary and fiscal policies in the developed economy, the healthier developing countries are seeing their currencies rise and endanger their own economic revival from the synchronized global recession. The depreciating US dollar caused by a flight away from dollar denominated assets, and a continuing monetary expansion does not bode well with our trading partners. As anecdotal evidence, gold continues its unstoppable advance as the holder of value. During the G-20 meeting in South Korea this month, the members promised to refrain from weakening their currencies, agreeing to let the markets exert more influence in setting foreign exchange rates. This temporarily dampens a wave of protectionism against countries that weakened their currencies in order to export their way to financial health. Although there seems to be more consensus than expected at the G-20 Summit, the G-20 lacks binding authority. The members also pledged to “pursue the full range of policies conducive to reducing excessive imbalances”. China remains the biggest obstacle. China, the second largest economy in the world, pegs its currency to the US dollar thereby keeping the value of its own currency artificially low. This is essentially a subsidy to China’s exporters. This has enabled China to flood the U.S. and the world with low cost goods. Strain is showing among the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations. They have seen a significant rise in their currencies against the Chinese Yuan. This will continue to put pressure on this group of export and China dependent economies. Nonetheless, for domestic political and economic stability, China is not likely to allow its currency to appreciate dramatically. The most likely scenario is the gradual and contained appreciation over time.

The U.S. markets have rallied significantly in the third quarter. With the exception of the U.S. dollar, almost every asset class has appreciated, which is very unusual. The stock market continues its advance into October banking on a Republican takeover of the House and a reasonably large QEII. Even as the stock market advances, more investors have moved into bonds in the third quarter – $42.8 billion went out of U.S. stock funds while $87.7 billion went into bond funds. This is one indication that investors remain cautious (even though at the present bond yield, one could suggest that the risk is greater in bond than in stock investments). Another indicator is that corporate balance sheets are flush with cash. Companies remain guarded about the U.S. and global economic recovery and the political and regulatory domestic uncertainty. If consumers are not spending and deleveraging and capacity utilization remains depressed, companies are less likely to invest and hire. It seems that everyone is waiting in a holding pattern.

In July, Chairman Bernanke in his testimony to Congress said that “the economic outlook remains unusually uncertain”. Although the first round of QE helped to stabilize the U.S. economy at a critical time, more of the same may produce little result this time. QEII may offer a temporary psychological boost, but it will likely have little to no effect on stimulating the economy and expanding the economy. When consumers (representing 2/3rd of the U.S. economy) are in a defensive mode and would rather pay down debt and save their income, additional money pumped into banks for lending will not make any difference. Although fixed income investing is not in danger at the moment, soon or later rates will rise and bond holders will bear the cost of depreciating bond prices and reflation.

Ever since the first QE, the Federal Reserve has inadvertently pushed investors to embrace rick. Most investors are not satisfied with the paltry yields on short-term fixed income securities. The Federal Reserve policy is driving investors to buy bonds with higher duration and lower quality (as compared to U.S. treasuries) in order to add liquidity and activities to the rest of the fixed income universe. QEII further cements this approach and solidifies the belief that the Federal Reserve will maintain an accommodative posture for an extended period of time. As such, we do not expect short terms rates to rise in the next 18 months. Of course this assumes that the U.S. economy continues its current slow growth posture. However, this cannot be said for the market driven long-term rates. Even if a portion of the QEII is used to purchase long dated securities, market forces will drive the interest rates higher if investors become more concerned about inflation and U.S. credit risk. Treasury Inflation Protection Securities have been on the move since late summer which is one sign suggesting the market is beginning to expect inflation down the road. In the near term, high yield bonds, floating rate bank debts and emerging market debts (local debts and bonds) are expected to perform well, and, on a relative basis, stocks as an asset class look increasingly more attractive. With many dividend yielding stocks paying a higher yield than bonds, income investors are beginning to find them to be attractive alternatives.

The outcome of the U.S. mid-term election, the Federal Reserve’s actions, and the decision regarding the Bush Era tax cut are all near term risks to the market. The exact impacts on the market remains uncertain.