This third quarter outlook addresses three global macro risks. These are risks and events that we observe daily and their effects can be cumulative making the impact potentially significant in the near term. Although the contributing factors that may form the next financial crisis are not exactly the same as the ones responsible for the financial crisis of 2008-2009, the impact can be equally, if not more, serious. The last crisis, which originated in the U.S. and culminated with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers was arrested by the coordination of massive and unprecedented financial and monetary efforts globally. A severe recession in the developed economies ensued. Sovereigns and monetary authorities injected significant amount of liquidity into their economies and recapitalized their banks by swapping toxic assets with cash infusion. The smoke-and-mirror deleveraging process was initiated. Consumers and private sectors began transferring their debts to the sovereigns and super-sovereigns. Much of the developed economies are now facing high unemployment coupled with the prospect of a decade or more of low economic growth and disinflation. Central banks are maintaining a close to zero interest rate policy in an effort to stimulate the animal spirit. In the U.S. the monetary policy of quantitative easing through Federal Reserve’s large scale security purchases (QE1, QE2 and more recently “Twist”) have become increasingly ineffective after an initial boost of euphoria. We are in a liquidity trap where lowering interest rates and expanding the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet contribute little to stimulating economic growth and aggregate demand. In a time of deleveraging and macro uncertainty, the private sector is not looking to borrow, build, spend, hire, or invest. It is with this backdrop of a constant borderline recessionary economy, ballooning sovereign debt, and impotent policy responses that the next financial crisis is brewed. Regardless of whether the next crisis will be fully realized, this Age of Great Consequences shall remain with us for years to come. Developed economies will pay through lower standards of living, higher taxes, less entitlements, and the continuing erosion of the middle class.

We are now faced with a severe European sovereign debt crisis, the threat of a new synchronized worldwide economic slowdown, and U.S. legislative and regulatory paralysis resulting from the escalating divisiveness and political rankling in preparation for the 2012 U.S. election year. These events add significant uncertainty to the already fragile global economy and further dampen the desire to take risk on every level. In the U.S. the uncertainty of implementing the full Dodd-Frank Act and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the omnipresent trial ballooning of manipulating the corporate and individual tax codes are a death knell to reviving the corporate animal spirit in the U.S. The biggest risk going forward is not fiscal or monetary but political. The major world economies are being held hostage by policymakers and political parties whose actions, interests and agendas often are not aligned with the long term best interests of their people or countries.

The European Sovereign Debt/Liquidity/Banking/Confidence Crisis

It is no secret that the developed economies of the world have been on a debt binge for years. In 2007, the music stopped and the party came to an abrupt end with the bursting of the real estate bubble which led to the deepest and longest recession since the Great Depression. The source of the crisis was the U.S.; the contagion was the toxic asset of sub-prime mortgages, and the transmission mechanism was the interlinked worldwide banking and shadow banking system. With the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and the collapse of Bear Stearns, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, AIG and the countless institutions in the shadow banking system, the domino effects were felt throughout the banking and financial world. Interbank lending [1] froze up and it took a three quarter of a trillion dollar Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP transferred toxic assets from the banking and private sectors to the public sector, thereby recapitalized the banks), billions of additional dollars from special programs, and an unprecedented expansion of the Federal Reserve balance sheet to stabilize the U.S. banking and financial system. After conducting a series of comprehensive stress tests, confidence was mainly restored to the U.S. banking system. Europe was also significantly affected during the mortgage crisis with its own real estate bubble and many of its financial institutions held toxic assets that were believed to be rated as investment grade assets and also suffered from counterparty risks. In a similar manner, much of the European toxic assets migrated onto sovereign balance sheets. Recession and economic slowdown ensued globally which saw GDP plummet and tax revenues shrink while costs of social programs ballooned. The debt to GDP ratio further deteriorated, and investors and bondholders began to question if the sovereigns with the highest public debts would be able to meet their debt and interest payments.

For almost two years, European policymakers have taken a series of baby steps in dealing with what was perceived as a localized Greek sovereign debt crisis without a full recognition of the possible rippling effects caused by market psychology and the complex nature of cross-border connectivity. European policymakers hoped that, given enough time, the high debt European states would partially grow their way out of their debt problems thereby lessening the response from the other eurozone member countries.

Now the crisis is on the verge of morphing into an explosive contagion that will not only bring down European banks but have significant global ramifications. This growing crisis is often referred to as the sovereign debt crisis, the liquidity crisis, or the banking crisis. These are all accurate terms in describing its manifestation, but they do not represent its perpetuation. This is a crisis of confidence.

A vicious sovereign debt cycle starts with the questionable ability of a sovereign in meeting its public debt obligations. This leads to falling bond prices and increasing borrowing costs to rollover the national debts upon maturity. The graph below shows the 10-Year Sovereign Bond Spread illustrating interest rates of PIIGS since the beginning of 2010. The escalating interest rates demanded by the bondholders increase the burden to the countries servicing their debts. Credit rating agencies attempting to stay ahead of the credit cycle began to downgrade their sovereign bonds[2]. This further weakened market confidence in the sovereign’s ability to meet its debt obligations.

Interestingly, much of the recent sovereign debts was piled on by the recapitalization of the banking system and the crisis provoked recession. Even though the bad debts were moved from the banks’ balance sheets to the public balance sheets, banks are in turn the large holders of sovereign debts in Europe. With sovereign debts being systematically repriced, banks watch their asset values dwindle and their capital and reserves erode. This leads to credit watch and downgrades on banks by rating agencies[3] which in turn leads to bank solvency concerns, bank runs and freezing of the interbank lending market. These outcomes are not confined to a region or a few European institutions since interbank lending and credit default swap markets[4] are interlinked among banks and financial institutions globally. The contagion can quickly spread to other money center banks around the world. Sensing this, sovereigns and super-sovereigns got involved to shore up the financial positions of banks just at a time when they are themselves up to their elbows in debt.

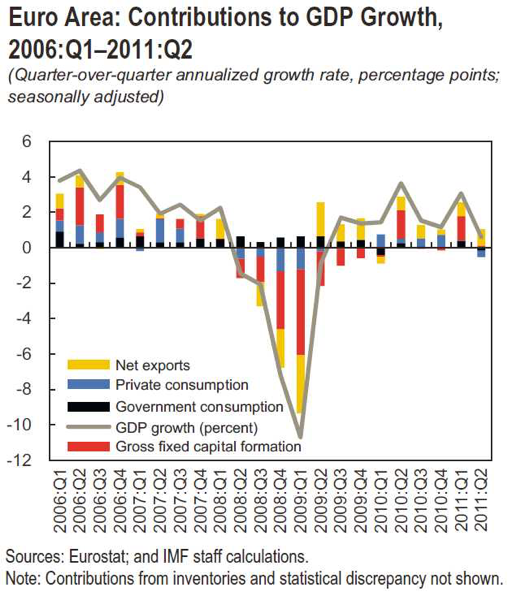

In a seemingly logical response, high debtor governments initiated a series of unpopular austerity measures of raising taxes (generating income) and cutting government spending (reducing expenses) in an effort to bring the public debt to GDP ratio in line with market expectations. These actions led to a serious economic slowdown or recession which further shrank the GDP and exaggerated the debt to GDP ratio. The graph below illustrates the shrinking private and government consumption with literally no gross fixed capital formation which is contributing to a significant economic slowdown in the eurozone.

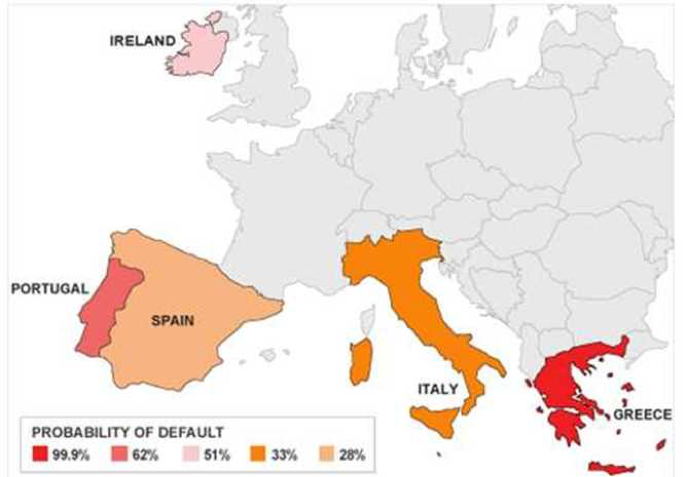

A self sustaining feedback loop is now in place as market confidence continues to slide and borrowing costs continue to rise. Unless and until a sufficiently large exogenous event or effort that would knock the cycle off track or stop the cycle from widening and spinning further downward, the feedback loop will gain strength and the sovereign debt crisis will quickly expand. Greece is in the eye of the storm, with Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy spinning in its vortex. The challenge is to regain the confidence of market participants and bondholders to continue to lend or allow the current debts to rollover at normal terms.

The reality is that, with the exception of Greece and Ireland where their debts have surpassed the tipping point (hence sovereign debt crisis), most of the countries have the ability and capacity to service their current sovereign debt, but, due to increasing doubts in the market, these high debt countries are not able to refinance their debts at reasonable rates (hence liquidity crisis) which would eventually lead to a sovereign default.

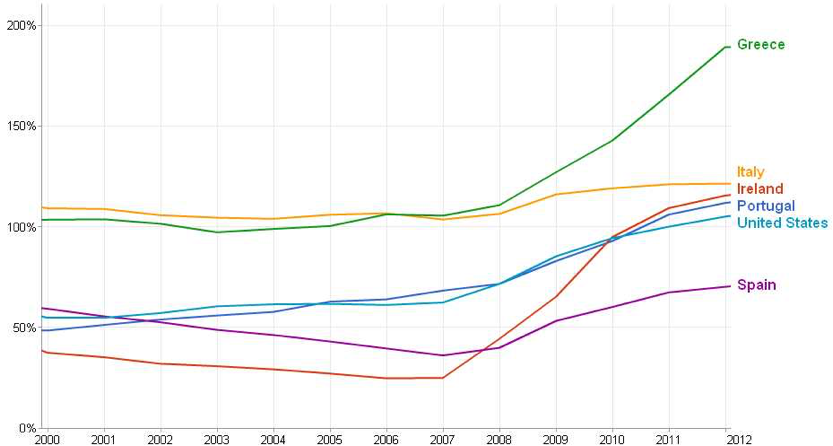

The chart on the next page shows the escalating general government gross debt as a percentage of GDP (International Monetary Fund, September 2011 World Economic Outlook). There is little doubt that Greece will default on its sovereign debt within the next 9 months. The first question is will the bankruptcy be structured (i.e. pre-organized and agreed to with debt holders) or unstructured. The second question is that, if it is organized, what will the haircut be (i.e. how much principal and interest rate reduction will the bondholders be willing or expected to accept and the extension of repayment terms). The reduction range discussed is from 20% to 60%. The third question is will the “ring-fencing” or “fire wall” that the policymakers are contemplating be large enough to fence off any contagion fall out (i.e. will the market have confidence that the sovereign debt crisis will not also consume Spain and Italy).

At the October annual meeting of the IMF and World Bank in Washington this year the Europeans agreed to a three-prong plan: 1) a plan to ring-fence solvent but illiquid economies (i.e. Spain and Italy), 2) beef up new capital or leverage up the main bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility[5] (EFSF), and recapitalize Europe’s banks, and 3) prevent a Greek default. Even though this three point plan demonstrates the urgency and understanding of the growing European sovereign debt challenge, there has been no agreement on any of the details of such a plan. This is another meeting where the policymakers plan for another plan.

The problem is that the 17 countries in the eurozone are not a single entity. Since the beginning, these countries only agreed to a European Monetary Union (“EMU”) with an understanding to a set of fiscal benchmarks[6]. Even though the currency is unified, each country has its right to its own economic, fiscal and tax policies. No one country wants to be responsible or liable for the debt of another country. In fact, it is often not deemed to be in their national interest to do so. Each of the 17 members of the EMU has the right to veto on any key decisions, which must also be ratified by their parliaments. The whole eurozone decision process is messy and time consuming. Case in point., on October 11, the Slovak parliament rejected the request for new powers for the €440bn EFSF. Three days later, after the collapse of the four-party coalition government, Slovakia became the final member of the EMU to approve the overhaul of the eurozone rescue fund.

The lack of a fiscal union and redistribution mechanisms in Europe will continue to pose problems in solving the current sovereign debt crisis, and continue to challenge and frustrate those who believe in a single Europe with a single currency. In the case of Greece, being a part of the single currency system prevents it from devaluing its own currency (which no longer exists) to inflate their way out of the sovereign debt crisis by paying the bondholders with a cheap currency. Greece and Europe have two options. The first is for Greece to remain in the EMU and look to other sovereigns and super-sovereigns to continue supporting its debts and financing needs while enforcing a series of severe austerity programs. This approach requires the consensus of the remaining eurozone members and depends on how well the policymakers can “ring fence” or “fire wall” the crisis to Greece only. The real problems are credit-freeze-led default of Spain and Italy due to delayed actions by the eurozone countries. The second approach is to allow Greece to structure a default and/or leave the EMU. Either approach will be painful, but the alternatives are much worse.

The G-20 meeting this weekend attended by the finance ministers and central bank governors of the 20 largest world economies was again long in rhetoric and short in action. The G-20 offered support to the Europeans and urged them to work decisively and speedily to restore confidence, financial stability and growth to their region. The Europeans in turn affirmed that they will have a comprehensive plan to resolve the Greek sovereign debt crisis, recapitalize systemically important banks, and beef up its funding to avoid a financial crisis. They agreed to come up with the grand plan by the next EU Council meeting one week hence. A five-point plan is in the works for the next meeting: increase the financial power of EFSF, provide new capital for banks, push to boost competitiveness and consider European treaty changes to tighten economic management. This sounds like another plan for a plan The following is a list of more upcoming meetings by which the policymakers can “kick the can down the road”, but how long will the market be willing to sit by patiently and silently?

23-Oct: EU Council Meeting (postponed from 18-Oct)

24-Oct: EU, IMF & ECB Review of Greek Finances

3/4-Nov: G20 Summit

7-Nov: Euro zone Finance Ministers’ Meeting

29-Nov: Euro zone Finance Ministers’ Meeting

9-Dec: EU Council Meeting

1/2-Mar 2012: EU Council Meeting

U.S. bank exposure to the European debt crisis is estimated at $640 billion, nearly 5% of total U.S. banking assets, according to recent research papers written for Congress. This does not seem to be too much and should have little impact on our banking system, especially now that our money center banks or systemically important banks are some of the most well capitalized banks in the world. However, depending on how well or poorly the Europeans handle the Greek default and their ability to ring fence Spain and Italy from a sovereign default, the impact can be significantly more series. Based on two different reports provided to federal lawmakers last month, the debt problems of PIIGS constitute a ”serious risk” to the European banking system, particularly German, French, and U.K. banks, which have close ties to U.S. banks. “Given that U.S. banks have an estimated loan exposure to German and French banks in excess of $1.2 trillion and direct exposure to the PIIGS valued at $641 billion, a collapse of a major European bank could produce similar problems in U.S. institutions.”[7] “The estimate doesn’t include U.S. bank exposure to European bank portfolios that include assets in the weak member countries. Also, it doesn’t account for euro-zone assets held by money market, pension, and insurance funds.”

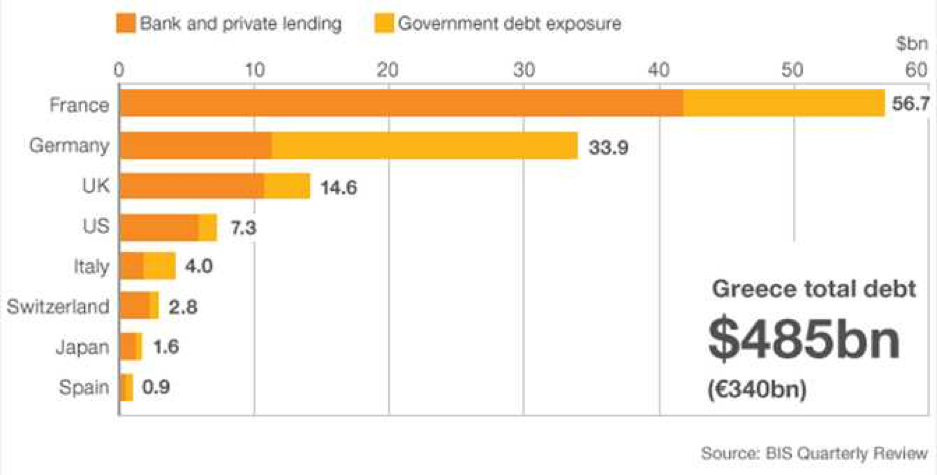

According to the Bank for International Settlement, the following is the estimated total bank lending exposure to Greek banks and the government as of June this year.

| Country | Total lending exposure to Greece (millions) | Total Government debt exposure to Greece (millions) |

| Total of 24 countries | 145,783 | 54,196 |

| European banks | 136,317 | 52,258 |

| Non-European banks | 9,466 | 1,938 |

| France | 56,740 | 14,960 |

| Germany | 33,974 | 22,651 |

| Italy | 4,085 | 2,345 |

| Japan | 1,631 | 432 |

| Spain | 974 | 540 |

| UK | 14,060 | 3,408 |

| US | 7,318 | 1,505 |

Source: BIS Quarterly Review [8]

The world banking system is linked and how and what happens in Europe have a direct impact on the US and the world economy. Greek default is a certainty. How and when the eurozone finally handles this event can lead to a mild and shallow recession or an economic depression.

The World Economy

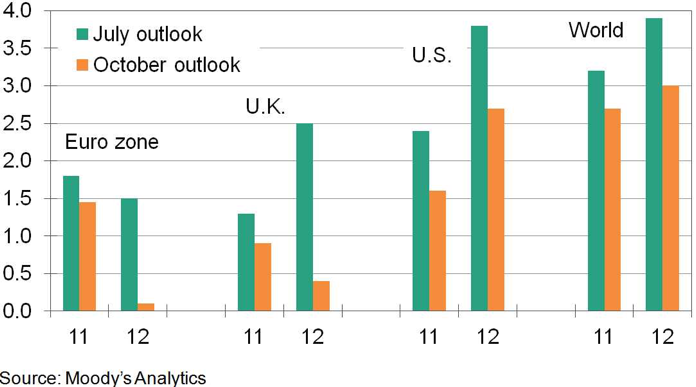

The world is slowing and the fear of another recession in the US and Europe is in the air. According to the latest revisions from Moody’s, every world region is expected to grow slower, a growth recession if not a real recession.

The Pimco coined term, the New Normal, remains the current and base case for the developed world or G3. This is a world with significant structural issues that caused high and sustained unemployment and underemployment and low economic growth. The consumers continue to deleverage in an effort to repair their balance sheet while increasing savings. Housing remains a problem with overall prices continuing to drift downwards causing more equity erosion across the board. Although banks are much healthier today, credit remains difficult. The recent stock market selloff has further contributed to an overall drag on the economy.

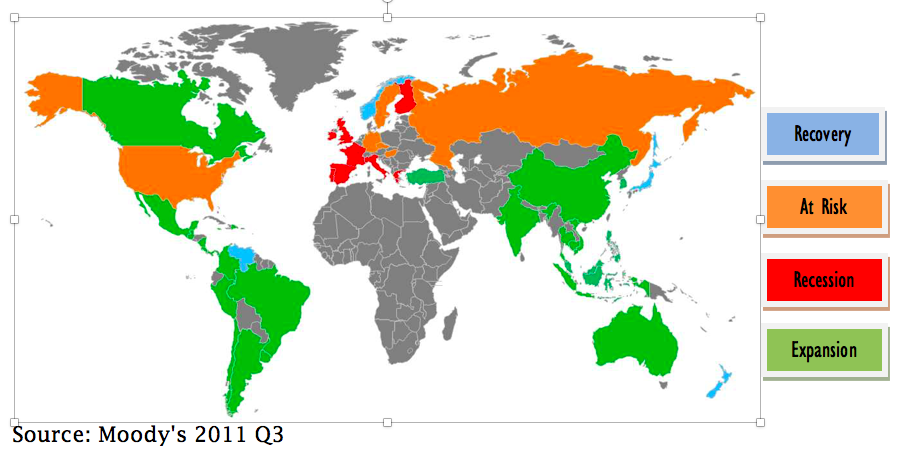

According to Moody’s, the developed world is either in recovery, at risk of falling into recession, or in a recession. In the case of Europe, with few exceptions, most countries are in or teetering on falling into a recession. The depth and breadth of a pan-European recession or economic contraction will be dependent on how the European sovereign debt crisis is managed and how quickly the solution can be agreed upon and implemented. It is no secret that an austerity program of increasing taxes, cutting government expenditures, lowering entitlement benefits and laying off civil servants is a recipe for economic contraction. With very little hope for growth in the eurozone, which is the largest single market in the world in terms of GDP, the rest of the world economy will also be affected.

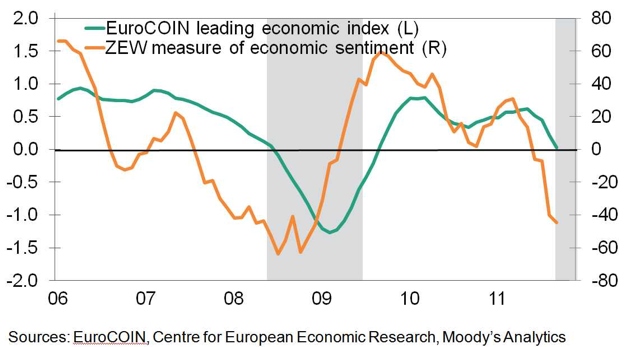

Although core-Europe is not in a recession now, Germany and France, are showing signs of significant slowdown. GDP in the 17-country eurozone rose 0.2% in the second quarter, according to Eurostat, after a positive reading of 0.8% in the first quarter. German GDP slowed to 0.1% from 1.3% in the first quarter, and the French economy did not grow at all in the second quarter. Services expansion in the euro zone lowered to 51.1 in August from 51.6 in July, following the contraction of manufacturing to 49.7 from the prior expansion of 50.4. Accordingly, PMI composite (Flash Markit Eurozone Services Purchasing Managers’ Index) fell to 47.2 in October following a reading of 48.8 in September, 50.7 in Aug and 51.5 in July[9]. The September and October PMI numbers show that the eurozone is trending into a recession.

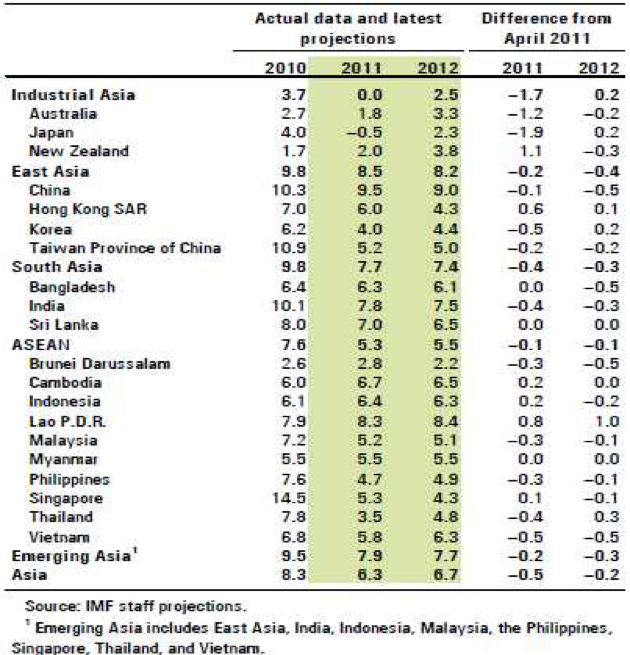

Chinese HSBC services PMI shows an ease in expansion to 50.6 in August from 53.5 in July but 51.1 in October, up from 49.9 in September[10]. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s third-quarter economic statistics showed the lowest GDP growth rate in the past two years. China’s GDP growth rate during the third quarter edged down to 9.1%, from 9.5% in the second quarter and 9.7% in the first quarter. The deceleration in foreign demand, substantially influenced by the lingering financial crisis in the developed economies, has contributed to China’s economic slowdown. The trade surplus in September decreased by 12.4% from a year earlier to US$14.5 billion and has seen its shipment growth to its largest export market Europe more than halved from 22% to 9.8%. On the other hand, China’s domestic economic engine remains robust. However, endogenous dynamics are not sufficient to overcome exogenous factors if the rest of the Chinese export markets continue to slow or run into a recession. China’s inflation at 6.1% continues to be of concern. The following chart summarizes the IMF’s revised projection for Asia’s real GDP (year-over-year % change):

The revision from IMF’s April estimate is generally revised down for 2011 and mostly revised down for 2012. The 2012 revision is based on the base case for a muddled through European debt crisis.

According to the IMF’s October 2011 World Economic and Financial Surveys Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific, it states that the “[n]ear-term risks to the forecast are tilted decidedly to the downside, more so than they were six months ago. A worsening of the financial turbulence in the euro area poses an extreme downside risk for Asia. The panic sell-offs across Asian financial markets and safe-haven flows into Japan that occurred when European troubles intensified in August-September 2011 demonstrate that there is “no place to hide” when advanced markets come under pressure. Asia may be affected through several channels, including:”

- Liquidation of foreign investor positions,

- Repatriation of liquidity by European banks, and

- Loss of market liquidity in key derivative markets

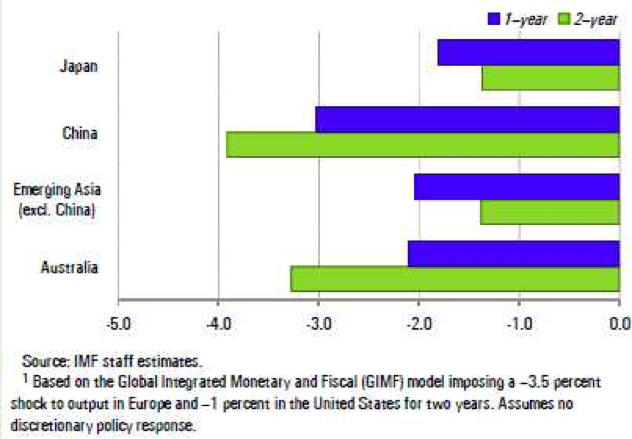

“In addition to these direct channels of financial contagion, Asian economies would be greatly affected if greater financial stress in Europe were to lead to a severe economic contraction in the euro area and the United States. In addition to standard trade-channel effects, such a shock would exert substantial knockon effects on domestic demand, in particular investment. Staff estimate that, in a severe global downturn scenario where growth in the European Union falls by 3½ percent below the current baseline for two years leading to a 1 percent slowdown in U.S. growth over the same period, GDP growth in the Asia and Pacific region could fall by 1½‒4 percentage points relative to the baseline, in the absence of policy responses.”[11] The above table shows IMF’s projection for impact of a severe global slowdown on real GDP growth (percent deviation from baseline scenario) for Asia.

For the US, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) looks to four variables to determine if we are in a recession: personal incomes, employment, industrial production, and business sales. We know that personal income and employment remain weak, and signs indicating industrial production, and business sales remain weak as well. NABE’s October 2011 Industry Survey indicates expectations are muted, but growth remains the base-case scenario “The breadth of industry sales growth narrowed in October, but there are still significantly more firms reporting rising sales than declining sales. Expectations for economic growth decelerated, but 97 percent of firms still expect positive economic growth in 2011. The European crisis has negatively impacted firms’ sales in 2011, but more firms are reporting increased profitability in the quarter. The survey indicates companies are still building for an improving future. The number of firms adding employees dropped in October, but there are still more firms looking to add jobs than to cut them. Capital spending also increased for a ninth consecutive quarter. Despite a narrowing of positive indicators, the majority of respondents remain cautiously confident.”[12]

The latest ISM survey results show a mixed economic picture of the U.S. but very much in an anemic growth environment. According to Moody’s Economy.com:

- The ISM manufacturing index was stronger than expected in September, rising from 50.6 to 51.6. This is only the second monthly increase in the past seven months but leaves the index at its highest since June. Production rebounded in September while the employment index added 2 points to 53.8. The trade details were positive and suggest exports will provide a decent contribution to third quarter GDP growth. Leading indicators remain weak as new orders were unchanged at 49.6. This is the third consecutive month that new orders have been below their expansionary threshold of 50. Manufacturing isn’t booming, but it’s also not collapsing.

- The ISM nonmanufacturing index held up fairly well in September, falling from 53.3 to 53. The business activity index rose from 55.6 to 57.1 for September. The details were generally mixed; new orders rose 3.7 points to 56.5. This is a positive for growth this quarter. Backlog orders broke back above their neutral threshold of 50 for the first time since May. There were some disappointments as new export orders fell 4.5 points and the employment index dropped below 50 for the first time since 2010.

Although there is no certainty that the US will be in a recession within the next 9 months, there seems to be a high probability that the eurozone will be dragged into a recession by the austerity programs implemented in the peripheral economies. The developing economies will continue to be the driving engine for world growth. This base case scenario is predicated on no further shock coming from the European sovereign debt crisis.

U.S. Debt Ceiling Deal in August – Just The Beginning

The Budget Control Act (a.k.a. the debt ceiling deal) passed by the House on August 1 and by the Senate the day after narrowly kept the U.S. out of default and agreed to reduce deficits by at least $2.1 trillion over 10-years. In exchange for the debt reduction, the debt ceiling was allowed to increase by between $2.1 trillion and $2.4 trillion to cover Treasury’s borrowing needs until 2013. During the next 10 years, the new law intends to accomplish a $917 billion in deficit reduction by capping the amount of money Congress can spend in annual appropriations bills without providing specific budget cuts. Additionally, a new bipartisan congressional committee was formed (“Super Committee”) to propose ways to reduce deficits by between $1.2 trillion and $1.5 trillion. If the Super Committee fails to do so by November 23 or Congress fails to enact the committee’s proposals by December 23, up to $1.2 trillion in across-the-board cuts would be automatically implemented and evenly divided between defense and non-defense spending. If this is triggered, the auto cuts will not apply until the 2013 fiscal year. This will allow Congress more time to develop an alternative solution before the caps take effect.

Based on the membership of the Super Committee, also referred to as the Gang of 12[13], in a politically charged and divisive environment, it is not certain that an agreement will be reached. This means that there is a possibility that the automatic cut will be enacted. This allows the budget to be trimmed in theory without each side having to take on political risk while proclaiming their faithfulness to their beliefs. Also this will in effect kick the budget decision to the election year. Regardless if a proposal comes out of the Super Committee or if the automatic cut is defaulted into action, the U.S. may be subject to another round of bond downgrades.

Separately, the new fiscal year stated on October 1, 2011, and already another government shutdown is possible by November 18. Last year, Congress failed to enact any annual appropriation bills which are needed to fund non entitlement government operations. Congress has relied on continuing resolutions to fund government operations since. The current continuing resolution expires on November 18. With the Budget Control Act in place, we hope the annual appropriation bills or another continuing resolution will be pass with less contentious debates and fanfare.

Conclusion

The October 22 EU Council meeting is on its way. This is the 13th crisis-management summit in 21 months and the exact plan will not be “ready” until the next summit on Oct. 26, which will start with all 27 EU leaders before the 17 heads of euro economies meet on their own. Sounds like this weekend is to be spent planning for another plan without any final action. The problem is mainly political, and in fact, the longer this “plan to have a plan” process continues, the larger the problem becomes and fewer and more exaggerated the solutions become.

EU and the policymakers are quite ready to abandon Greece if they have any certainty that Spain and Italy will not be the next targets. Unlike the U.S., European banks have always been an instrument of their governments. The sovereign debt crisis is a banking crisis. The two of the three prong approach of bank recapitalization and debt restructuring (i.e. structured default) for Greece are two of the same. The larger the haircut required for sustainable debt relief, the larger the losses to the banks and the larger the injection of capital to banks for recapitalization is needed to shore up the market confidence to avoid a Spain and Italy default.

The solution is simple: much more money. The base case for Europe is that later, rather than sooner, the 17 countries will agree to take the necessary actions to contain the sovereign debt crisis. It takes time for the less indebted countries or countries with stronger economies to be willing to transfer payments (directly or through intermediaries) to the PIIGS. Right now, there is no fiscal union where Germany will de facto dictate terms for the rest of Europe, euro bonds, additional contributions to the ESFS, huge haircuts on Greek bonds for a structured default, and more funding tranches unless and until the PIIGS are able to demonstrate that they are meeting their austerity conditions in their home countries. The core European countries will not act decisively and aggressively until the entire eurozone and the euro are ready to collapse. We just hope that their actions will not be too little and too late. The Sunday NY Times published a schematic showing how the world is linked financially to the sovereign debt crisis: It’s All Connected: A Spectator’s Guide to the Euro Crisis. [14] This is a quick way to get a top down view of how the sovereign debt/banking crisis can travel like a virus and infect the world financial system.

The developed economies have barely recovered from the last recession with the help of massive and unprecedented fiscal and monetary support, and are again facing recession. I believe that most of the recovery from the last recession was artificial and temporary. The current anemic economic environment is evidence that the handoff from the government to the private sector remains fragile and insecure. In the U.S., housing problems remain unresolved, Federal regulations and lawsuits are causing banks to be more cautious and less able to make credit easily available, structural unemployment remains a huge challenge, and consumers remain too much in debt and continue to delever. The current political climate makes any stimulative fiscal policy virtually impossible, and in fact, federal, state and local governments are cutting or looking to shrink their budget further. It is common knowledge that 2/3rd of our economy is made up by consumer spending and 20% is made up by the government sector. Under these circumstances, growth will continue to be muted and a shallow and short recession is not out of the question. At the projected US GDP of 1% to 2% per annum, it would not take much to fall below 0%. The magic potion is growth. Everyone talks about how the PIIGS countries must focus on growth so that they can recover and support their debt in the long run, otherwise we will experience a rolling sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The reality is that the developed economies are shrinking due to austerity programs and there are no local or domestic economic growth engines. Every economy is looking to the developing world.

The U.S. is entering the election season for 2012. Each party is lining up to differentiate itself from the other, and this typically means political attacks and show perceived strength through stubbornness. We do not expect much to be accomplished before next November and we may have to endure another round of downgrading of our debt and another year of regulatory uncertainty. The biggest risk remains with Europe. Depending on the politicians’ willingness to make tough and timely decisions, the world economy will be further affected.

Investing in this environment is difficult. The market participants pay no attention to fundamentals while perceived macro risks reign supreme. From historical and relative standards, many risk assets are of great value while US Treasuries are at historical lows and carry great risk. Until there is a more permanent clarity with the European debt crisis, the recent risk on and risk off market globally will continue. Portfolio diversification does not produce any benefits under this environment, and in the short run, only a few assets can shelter portfolios from erosion.

What is most troubling is that the world economy rests in the hands of politicians. Their actions or inactions, intended or otherwise, will shape the course of economic lives for billions. Our rational base case of politicians will do the necessary and right things may not happen. This reminds me of the nine most terrifying words in the English language according to President Ronald Reagan in 1986: “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help. ”

[1] The interbank lending market is a market in which banks extend loans to one loans are for maturities of one week or less, the majority being overnight. Such loans are made at the interbank rate (also called the overnight rate if the term of the loan is overnight). Low transaction volume in this market was a major contributing factor to the financial crisis of 2007. Banks are required to hold an adequate amount of liquid assets, such as cash, to manage any potential withdrawals from clients. If a bank cannot meet these liquidity requirements, it will need to borrow money in the interbank market to cover the shortfall. Some banks, on the other hand, have excess liquid assets above and beyond the liquidity requirements. These banks will lend money in the interbank market, receiving interest on the assets. Interbank loans are important for a well-functioning and efficient banking system. Since banks are subject to regulations such as reserve requirements, they may face liquidity shortages at the end of the day. The interbank market allows banks to smooth through such temporary liquidity shortages and reduce funding liquidity risk. Funding liquidity risk captures the inability of a financial intermediary to service its liabilities as they fall due. This type of risk is particularly relevant for banks since their business model involves funding long-term loans through short-term deposits and other liabilities. The healthy functioning of interbank lending markets can help reduce funding liquidity risk because banks can obtain loans in this market quickly and at little cost. When interbank markets are dysfunctional or strained, banks face a greater funding liquidity risk which in extreme cases can result in insolvency. (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interbank_lending_market)

[2] Oct 7, 2011 Fitch downgraded Spain from AA+ to AA-, Italy from AA- to A+. New Zealand from AAA to AA+, Oct 5, 2011 Moody’s downgraded Italy from Aa2 to A2, Sep 20, 2011 S&P downgraded Italy from A+/A-1+ to A/A-1, Oct 21, 2011, S&P warned France for possible downgrade.

[3] Oct 14, 2011, Fitch Ratings downgraded the several Spanish banks., Sep 21, 2011 S&P downgrades seven Italian banks, Mar 29, 2011 S&P downgraded five Portuguese banks

[4] Credit-default swaps allow investors to hedge against debt losses or speculate on creditworthiness. A basis point on a contract protecting 10 million euros of debt for five years is equivalent to 1,000 euros a year. Swaps on Deutsche Bank jumped to a record 225 basis points on Sept. 12, and now cost 210 basis points, from 96 basis points on July 1, according to CMA prices. Credit Agricole rose to an all-time high 322 basis points this month and are now at 310, from 130 at the beginning of July. Contracts tied to SocGen’s debt jumped to a record 435 in September, from 128 at the start of this quarter and are now at 413, according to CMA. Source: Abigail Moses and John Glover, Bloomberg News – Sep 23, 2011 5:15 AM ET, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-09-23/french-german-bank-cds-wagers-surge-amid-spreading-crisis-in-euro-region.html.

[5] The European Financial Stability Facility is the eurozone’s temporary rescue fund, created in June 2010 with the mandate of safeguarding financial stability in the eurozone. It is a Luxembourg-registered company owned by the eurozone states. EFSF could issue bonds guaranteed by eurozone states for up to €440bn (£388bn) to raise money to loan to struggling countries. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is a permanent program which will replace the EFSF in 2013.

[6] Member states who wished to adopt the Euro were expected to satisfy 3 criteria in compliance with the Maastricht Treaty:

1) Total sovereign debt outstanding to be less than 60% of GDP

2) Annual budget deficit to be less than 3% of GDP before member states are permitted to join the EMU

3) A national inflation rate within 2% of the three best performing member states

[7] http://blogs.wsj.com/marketbeat/2011/10/07/us-bank-exposure-to-europe-could-be-640-billion-per-congressional-paper

[8] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/8578337/The-countries-most-exposed-to-Greek-debt.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2011/jun/17/greece-debt-crisis-bank-exposed#data

[9] http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/236364/20111024/euro-zone-business-activity-shrinks-further-in-oct-pmi.htm

[10] http://finance.ninemsn.com.au/newsbusiness/aap/8364749/china-manufacturing-hits-five-month-high

[11] http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/reo/2011/APD/eng/areo1011.htm

[12] http://www.nabe.com/publib/indsum.html

[13] Rep. Jeb Hensarling of Texas (Republican and committee co-chair): Hensarling — chairman of the House Republican Conference — served on President Obama’s debt commission but voted against it. He object to tax increases. The debate over taxes is expected to be fierce. Hensarling is likely to be vocally opposed to any new revenues.

Sen. Patty Murray of Washington (Democrat and committee co-chair): Murray chairs the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, and it is her job to recruit candidates who can beat her Republican colleagues. Her appointment has already drawn criticism from the Republican National Committee. She is a member of the Budget and Appropriations committees.

Rep. Chris Van Hollen of Maryland (Democrat): Van Hollen played a key role in the debt talks led by Vice President Joe Biden earlier this year, and is the ranking Democrat on the Budget Committee. A Pelosi acolyte.

Sen. Jon Kyl of Arizona (Republican): The No. 2 Republican in the Senate and a staunch advocate for the military. Kyl is a member of the Finance Committee and is a reliable conservative vote and opposed to tax increases. He has said he will not run for re-election and walked out of debt negotiations with Biden earlier this year after an impasse over increasing revenue.

Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts (Democrat): Kerry is best known on Capitol Hill for his foreign policy experience. He will lend his expertise on national security matters to the debate over cuts to military funding. He is a member of the Finance Committee and has spent 27 years in the Senate.

Sen. Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania (Republican): Elected to the Senate last year, Toomey was a prominent voice in the debate over raising the debt ceiling, arguing that the U.S. could prioritize its payments in the event of a debt ceiling breach to avoid a true default. In the end, Toomey voted against the debt ceiling bill that created the super committee. He sits on the Senate Budget and Banking committees, and is the former president of the staunchly anti-tax Club for Growth.

Sen. Max Baucus of Montana (Democrat): Baucus — chairman of the Senate Finance Committee — served on Obama’s debt commission. But Baucus voted against the final Simpson-Bowles recommendations because he said they cut too deeply into farm subsidies and would have changed Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security in a way he found unacceptable. Those same issues — changes to those entitlement programs — are likely to be a central part of any grand bargain to reduce deficits.

Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio (Republican): A former White House budget director in the Bush administration, Portman is a Senate novice and a member of the Budget Committee.

More moderate that some of his colleagues, Portman could be a key player in a compromise.

Rep. Xavier Becerra of California (Democrat): A senior member of the House Ways and Means Committee, Becerra served on the Bowles-Simpson debt commission. But he voted against the plan because he said it cut too deeply into discretionary spending and did not raise revenues to a high enough level.

Rep. Dave Camp of Michigan (Republican): Camp — the House Ways and Means Committee chairman — served on President Obama’s debt commission, but voted against it. He objected to the plan’s tax hikes and said it failed to address rising health care costs. An expert on taxes.

Rep. James Clyburn of South Carolina (Democrat): The third-ranking Democrat in the House and veteran of the Appropriations Committee, Clyburn maintains close ties to Pelosi. He also participated in the Biden debt reduction talks.

Rep. Fred Upton of Michigan (Republican): Upton chairs the House Energy and Commerce Committee. He has taken some moderate positions in the past, including attempts to decrease tax cuts in the George W. Bush administration.

(Source: http://money.cnn.com/2011/08/11/news/economy/debt_committee_members/index.htm)

[14] http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2011/10/22/opinion/20111023_DATAPOINTS.html?ref=opinion