Since the last quarterly report, the financial world has experienced significant turmoil that many compare to the Great Depression. What started as a subprime mortgage crisis considered to be well confined to a sub-section of the financial world has morphed into a global liquidity crisis that brought down many financial icons around the world. We witnessed the bursting of the real estate bubble which contributed to global deleveraging, ending up in a crisis of confidence and an extreme aversion to risk. The foundational element for the global economy to function is trust. Without the belief that the issuer of a security or the promise of the counterparty will stand behind their commitments, the financial system will cease to function. No one will take risk since the foundation of trust is brought into question.

When fear is omnipresent, the only logical investment would be securities of unquestioned safety – U.S. government bonds. Thus there has been a massive liquidation of every kind of investment and a rush into U.S. treasuries. The U.S. and foreign markets on average have lost over 50% in market value since the last peak in October 2007. We have now moved on from the subprime mess and liquidity scare and are beginning to acknowledge the likelihood of a severe global recession. The speed and the depth of the unraveling of the financial crisis is mind numbing. Investors and lawmakers continue to try to contain the tsunami and devise ways to minimize the damage. The negative feedback loop that started with the decline in housing prices spread and further aggravated the subprime borrowers from getting out of their mortgages. As housing prices declined, value of the underlying mortgage securities also declined. Compounding this realty is the fact that over the past few years, financial institutions have taken significantly leveraged positions on these securities. Now, the process of deleveraging, risk aversion and unwinding the mortgage based derivatives exaggerate the lost in value and led to bankruptcies of weak and illiquid financial institutions. Every promise is called into question. Financial institutions and investors liquidated good and bad assets en masse to make up for the staggering losses or to cover redemptions. This dragged down equity markets and severely affected non-financial sectors as well. When financial intermediaries become insolvent or unstable, their ability to guarantee payments (i.e. credit default swap issuers) is called into question. This chain of events is not just confined in the U.S. Many foreign institutions and governments have invested in the “toxic” assets, and the phenomenon has cascaded globally.

Where Have We Been

The following is a summary of some of the major events that have transpired recently as a part of the U.S. led global credit crisis. The process of government intervention and nationalization continues and there is no certainty that the crisis has been totally contained. We are at a point where the collateral damage is as significant as the causes of the credit and financial crisis.

On September 6, the Federal government seized control of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government sponsored enterprises that provide funding for almost three-quarters of new home mortgages. Collectively the two entities own or guarantee nearly half of U.S. mortgage outstanding. It has been noted that over $5 trillion of mortgage-backed securities issued by both entities are owned by central banks and foreign investors worldwide. The U.S. Treasury agreed to acquire $1 billion of preferred shares in each carrying a dividend yield of 10%, and pledged to provide as much as $200 billion to cope with heavy losses on mortgage defaults. The government received warrants that give rights to acquire up to 79.9% of each company for a nominal sum. With this action, the government is in control of the secondary mortgage market.

The unintended consequence is the loss of stock value for many banks and institutions that have been long time holders of their stocks. This negatively impacted the capital structure of a number of savings and banking institutions.

On September 14, 10 major commercial and investment banks announced that they would pool $70 billion of their own money to create a borrowing facility with Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase each committing $7 billion. The 10 institutions, which also include Citigroup, Credit Suisse Group, and Deutsche Bank, could tap the pool to help them ride out the crisis. The banks also said they are mutually committed to trying to mitigate market volatility.

On September 15, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. announced that it would file a petition under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code with the United States Bankruptcy Court. This announcement came at the heels of the decision by the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve to allow Lehman to fail. We are still feeling the rippling effect of this bankruptcy.

On the same day, Bank of America struck an all-stock deal to buy the 94-year old Merrill Lynch for $29 a share, or $50 billion. Merrill has carried on its books billions of hard-to-sell assets along with a large debt load. Since the credit crunch mid last year, Merrill’s assets continue to deteriorate. In July, Merrill sold $30 billion of collateralized debt obligations at 22 cents on the dollar and raised more capital in December. After Merrill realized the possible implication of a Lehman bankruptcy after weeks of market pressure on its stock price, the sale to Bank of America was negotiated in 48 hours.

On September 16, in an unprecedented step, the U.S. government seized control of American International Group by making a loan up to $85 billion in an emergency credit line in exchange for 79.9% equity stake in the company in the form of warrants. The two-year loan will carry an interest rate of London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor) plus 8.5%. The loan is secured by AIG’s assets. The combination of excessive exposure to credit default swaps, credit rating downgrade, inability to raise $75 billion from private-sector banks and rapidly falling stock price have contributed to the need for a bailout. U.S. regulators concluded that it would be catastrophic if AIG is allowed to fail.

On September 17, Primary Fund, the oldest and one of the largest money market mutual funds in the country with $785 million holding of Lehman Brothers debt, became worthless. The fund put a seven-day freeze on investor redemptions. The fund announced that it can no longer support the $1 net asset value and that they have to “break the buck.” This caused a significant turmoil in the money market fund industry since investors have always considered the money market funds to be safe because they invest in short-term high grade securities. No fund in the $3.6 trillion money-market industry has lost money since 1994.

On September 18, banks raised their inter-bank lending rates significantly, and many have even stopped lending to other banks causing a spike in the London Interbank Offered (Libor) rate despite central banks’ global infusions into the banking system. The overnight dollar Libor rose to 6.4375% from 3.10625%. This is unprecedented and reflects the extreme risk aversion in the market. The lack of faith in the system is punctuated by the AIG and Lehman fallout. AIG is a significant participant in the $62 trillion credit-default-swap market where banks and others buy and sell insurance against defaults on corporate bonds. AIG has sold insurance on hundreds of billions of dollars in debt to European banks alone.

It is clear to the only two remaining investment banks on Wall Street, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, that they are the next targets to fall. On September 19, they were successful in lobbying the Securities Exchange Commission to institute a temporary ban on short sale against financial stocks to prevent the continuous bashing by investors. The loss of confidence in the two firms was so severe that they needed to take drastic actions. The independent Wall Street model for investment banking is no longer viable for many reasons. One of which is the need for such firms to raise significant short-term cash on an ongoing basis to operate. Under these circumstances, the only logical and effective way to survive is to align with the U.S. government and to have access to available cash. Investment banks need to become a part of a commercial bank and seek the shelter of the Federal Reserve. On September 20, Morgan Stanley applied to become a commercial bank holding company, and by the next day it was approved by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This change is significant since the regulations for commercial banks are significant when compared to the SEC regulations for investment banks. Goldman Sachs followed in locked steps. Since then Morgan Stanley also reached an agreement with Misubishi UFJ to sell 21% of preferred stock for $9 billion while Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway invested $5 billion in Goldman Sachs.

On September 19, the U.S. Treasury agreed to insure, for a year up to $50 billion in money-market fund investments, financial companies that pay a fee to participate in the program. This initiative will in turn guarantee the funds’ values to maintain the $1 a share value. Additionally, the Fed will lend an unlimited amount to banks on a non-recourse basis to finance their purchases of high-quality asset-backed commercial paper from money-market funds. Furthermore, the Fed will purchase short-term debt issued by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banks from investment banks which would inject liquidity into the market.

On September 25, JPMorgan Chase agreed to acquire the banking assets of Washington Mutual after it was seized by federal regulators. In exchange for taking over $307 billion in assets and $188 billion in deposits, JP Morgan will pay approximately $1.9 billion to FDIC.

On September 28, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg injected $16.4 billion in the Dutch-Belgian bank and insurer Fortis NV. As a part of the bailout, Fortis agreed to sell its stake in the Dutch bank ABN Amro, which was partially taken over by Fortis last year.

On September 29, the British government nationalized Bradford & Bingley, a mortgage lender, by taking over its $91 billion mortgage and loan portfolio. The government paid out $33 billion to facilitate the sale of its savings business to the Spanish bank, Banco Snatander.

On September 29, central banks added $330 billion to funds that can be injected into money markets to stabilize financial institutions. The Federal Reserve doubled its currency-swap facility to $620 billion which allows foreign central banks to increase volumes of dollar-denominated lending to their banking systems.

On October 1, Ireland announced that it will guarantee all the debt of its top 6 financial institutions. This amounts to $563 billion in bank debt and individual deposits. Meanwhile, the Indian central bank stepped in to stop a run on its second largest bank, ICICI Bank Ltd.

On October 3, Governor Schwartzenegger wrote to U.S. Treasury Secretary Paulson putting the federal government on notice that California may need an emergency loan of up to $7 billion within weeks since the bond market is essentially frozen and CA is not able to raise cash to fund daily government operations and can’t access routine short-term loans it relies on to remain solvent.

On October 4, President Bush signed into law an unprecedented $700 billion plan to rescue the U.S. financial system after the original bailout package was defeated in the U.S. House of Representatives on September 30. The $700 billion would be disbursed in stages, with $250 billion made available immediately for the Treasury. In addition, another $110 billion in tax breaks over 10 years also passed.

On October 5, the German government announced that it will guarantee all private bank accounts and negotiated a $69 billion bailout for Hypo Real Estate, AG.

On October 7, the 27 nations that make up the European Union agreed to guarantee private deposits of up to €50,000 for one year and set guidelines on how each country could rescue failing banks. At the same time, the U.S. central bank announced that it will double its term auction credit facility to $600 billion. This allows the central bank to accept financial instruments such as mortgage backed securities as collateral from banks.

On October 9, Iceland, a $20 billion economy, suspended trading on its stock exchange and nationalized three of its biggest banks with $61 billion in unserviceable debt. These banks have been active in leveraged finance and have made significant loans to European industrialists. Separately, France, Belgium and Luxemburg agreed to provide a one year guarantee for all Dexia, SA, new loans and deposits after the initial cash injection of $8.8 billion failed to stop the share from a freefall. France becomes the largest shareholder with 25% ownership of the bank. Dexia is the largest lender to French local governments and ran into trouble because of its subprime loan loss and the bankruptcy of Lehman.

On October 10, the FDIC board approved the temporary increase per account limit to $250,000 and ceiling on joint deposit accounts to $200,000 per co-owner. The limit for retirement accounts held in banks remains at $250,000. This increase is extended through the end of next year.

On October 12, Wachovia agreed to be acquired by Wells Fargo after receiving final approval from the Federal Reserve two days earlier. Wells Fargo offered $15.1 billion without any government assistance for the entire Wachovia organization and out maneuvered an earlier $2.1 billion bid from Citigroup for just the banking business of Wachovia backed by the federal government.

On October 13, European governments have stepped in on a coordinated effort to stabilize their banking system. The U.K. is guaranteeing $434 billion of bank debt and injecting $64 billion into the Royal Bank of Scotland, HBOS and Lloyds TSB Group. The French government is guaranteeing $435 billion of senior bank debts and to create a state company with up to $54 billion to recapitalize or bail out banks. Germany is guaranteeing up to $544 billion of bank debts among banks, setting aside $27 billion for potential losses and injecting $109 billion directly into banks for ownership interests. Spain is guaranteeing up to $136 billion this year for new bank debt issues, setting up facilities to inject direct investment in banks for 2009 and allocating up to $68 billion to buy high quality bank assets. The Australia government also announced that it will guarantee all their bank deposits and banks’ wholesale term funding for inter-bank lending.

On October 13, executives representing 9 of the largest U.S. banks were given term sheets for the U.S. government to make direct investments of $125 billion in their banks without negotiation and to impose new restrictions on executive compensation and dividend policies. On the same day, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority agreed to guarantee all bank deposits up to HK$ 100,000 and to establish a new facility to provide capital to banks to boost confidence in banks. The new measures would be in place until the end of 2010.

On October 15, 27 European Union nations agreed to shore up their national banks and financial institutions by putting up guarantees totaling $2.3 trillion.

On October 17, the Switzerland central bank committed to take over $60 billion in toxic assets off UBS’ balance sheet while investing $5.3 billion in the bank in exchange for a 9% ownership. In the meantime, Credit Suisse Group raised $9 billion privately. Private banking customers withdrew a net $43.27 billion from UBS in the third quarter, and the Swiss government is open to the possibility of guaranteeing new debt issued by both banks going forward.

On October 20, South Korea announced that it will guarantee $100 billion in foreign-currency loans and inject $30 billion into its banking system as their banks and businesses face growing problems in obtaining foreign currency.

On October 24, Japan, China, South Korean and the 10-country Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agreed to establish an $80 billion emergency fund with Japan, China and South Korea contributing 80% of the assets. This fund allows any member nation to borrow when facing a liquidity crunch. The 13 nations set up bilateral contracts to supply funds through currency swap lines.

On October 25, PNC announced that the Treasury will buy $7.7 billion of preferred stocks and warrants and at the same time PNC will acquire the failing National City Bank. Capital One Financial and SunTrust Bank will sell $3.5 billion each of their preferred stock and warrants to the Treasury Department as a way to raise capital. Other regional banks also line up to get their share of government investments: Fifth Third Bancorp at $3.4 billion, KeyCorp at $2.5 billion, investment bank and asset manager Northern Trust Corp. at $1.5 billion, Huntington Bancshares Inc. at $1.4 billion and Comerica at $2.25 billion.

On October 27, the government of Belgium invested $4.4 billion for core capitals security of KBC Group NV, a Belgian bank and insurer, while not diluting the current shareholders. Meanwhile, Kuwait central bank structured a bailout for its largest bank and provided guarantees for all bank deposits in the country. Saudi Arabia is in the process of structuring a $2.3 billion loan facility for low income borrowers

Where Are We now?

The rolling financial crisis spreading from the U.S. to developed countries is now affecting emerging and frontier countries. The bursting of the real estate bubble lit the fuse to this crisis. The subprime mortgage debacle is often cited as the cause of much of the pain, the real culprit is deleveraging. After the burst of the Internet Bubble at the beginning of this decade, the Federal Reserve kept the interest rate low and contributed to an easy money environment. Furthermore, investors have progressively taken on risk to earn higher returns in an otherwise low return world. Borrowing and leveraging were pervasive and encouraged worldwide. U.S. consumers with perpetually escalating home values borrowed and spent. The emerging markets were more than happy to comply and feed the insatiable desire of the Americans to consume. With the rise of the developing economies, the commodity bubble began to be created. Raw materials of every kind are needed to satisfy exports and a growing domestic middle class. Inflation was on the rise and the U.S. dollar sank to multi-decade lows against other developing economies. As evidence of a U.S. economic slowdown mounting beginning in 2007, many speculators suggested that the world economy would decouple from the U.S. There was a real sense, or hope, that the economic engine of the emerging markets and the other developed economies would continue to grow at a reasonable pace while the U.S. economy slowed to a craw. This may have been a probable scenario prior to the financial crisis.

There seems to be no argument that we are in a recession in the third quarter. With unemployment on the rise and a continuing decline in real estate value, many economists are now suggesting a prolonged recession. This is an economic recession driven by a credit and liquidity contraction. This means a consumer recession that will persist for a long time. Without the home equity loan as the ATM machine and the increasing scrutiny of borrowers by lending institutions, credits will be hard to come by. Most U.S. consumers are carrying a heavy personal debt load and with stagnating wages, it will take a prolonged period of time before the consumers will be able or willing to expand their consumption. This does not bode well for the world economy. With the impending global slowdown, commodity prices have gone into a freefall with oil prices cut in half from their all time high of $147 per barrel. This speed of the reversal may be good news for oil and gas importers but it is disaster for the producing countries. When the commodity bubble was growing, the currencies of the producers, such as the Russian Rubles and the Brazilian Real, were gaining strength. These exporter countries have been awash in cash and invested aggressively. With the bursting of the commodity bubble due to the global economic contraction, they are experiencing a boom and bust cycle that significantly impacts their currencies and economies. Assumptions made even 6 months ago are revised repeatedly to adjust to the new global reality. Deleveraging of commodity exporters’ economies is as severe as in the developed economies and contributes to further downward pressure of asset prices worldwide.

In this uncertain world, flight to quality and massive abandonment of risk, perceived or real, rule the day. The small and new democracies of Eastern Europe are vulnerable and are the new legs of the current financial crisis. For nearly 20 years the former Soviet bloc countries have enjoyed massive inflows of western capital that generated wealth and prosperity, but with risk aversion, capital flight is particularly severe in this region of the world. Western European institutions are repatriating their assets quickly. The reversal of money and credit flow is pushing the Baltic States into recession. Their currencies continue to fall and liquidity dries up. This could quickly exacerbates the economic and financial challenges facing Western Europe. In fact, International Monetary Fund projects that all major European economies will enter recession in the coming months with the emerging European economies to prepare for a “hard landing”. The global economy is expected to expand at a 3.9% pace in 2008, down from 4.1% estimate in July. For 2009, the forecast is revised to 3% and is at the brink of a global recession.

Where do we go from here?

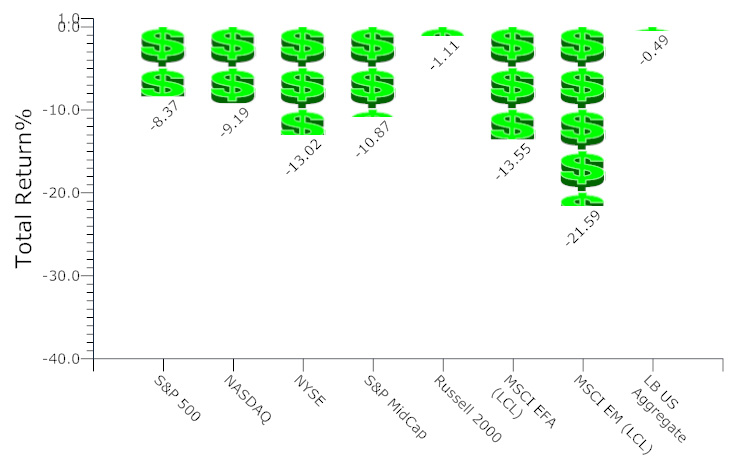

- Global Equity Return Suppressed

We are in a secular bear market for equities. With a prolonged recession in the U.S. and many developed economies worldwide, corporate earnings will continue to be weak. We will not return to the 80’s and 90’s where long term interest rates came down from double digits to single digit coupled with significant productivity gains. Assuming that the U.S. equity index has hit bottom, in order for the investor to make up the losses during this bear market we will need 5 years of continuous double digit returns. This is not likely. The growth engine of the global economy remains in the emerging market and as such, equity returns in these markets will likely to outperform the developed economies. Furthermore, with the complete and partial nationalization of many financial institutions, the ability and willingness to take risk are in doubt. As such, the expected return as a whole should be lowered. The risk pendulum has swung. We are going from one extreme to the other, and it will take a long time before it swings back. - Inflation Returning

The current deflationary condition is temporary. With the massive infusion of cash and credit by world central banks to avert a global depression, and the likelihood of a prolonged low interest rate environment, as the world economies recover, inflation will sure to follow. The current reprieve will be short lived and the long term inflationary trend will continue. The basic fundamentals for higher commodity prices from fuel to agricultural products remain intact. In this scenario, real assets will again be in favor since they are holders of value. Furthermore, with the U.S. deficit ballooning to unprecedented levels, it is the path of least resistance for the U.S. to pay back the national debt with depreciating dollars. This weak dollar policy would be inflationary. Higher production cost will be the norm and this is a long term inflationary factor. - Lower Fixed Income Returns

After the current rounds of interest rate cuts, interest rates will again be at a historically low environment globally. The only direction is for interest rates to rise. Fixed income returns are comprised of interest income and appreciation. The future environment will afford little appreciation since interest rates and bond prices have an inverse relationship. In the short term, however, with extreme risk aversion, many fixed income instruments are mispriced. When normalcy returns, these fixed income instruments will experience significant price appreciation as risk is again priced rationally. - Taxes Will Go Up

With all the noise being made during this presidential campaign season, it is a fairytale to believe that the U.S. can continue its current course either by a) raising taxes on the “rich” to afford new and expanding social programs for all or b) lowering taxes for the high income earners and create enough tax revenue to pay for our past sins. At the rate we are going, it will take many generations of belt tightening to pay down our national debt. This is even before counting the protracted economic slowdown and recession. Taxes, or by any other name, will have to increase. This will take away more disposable income from the U.S. consumers. - Regulation, Re-regulation and Nationalization

Free market capitalism is changed forever. The investment banking model is gone and in its place is the new superbank. This is the final realization of the end of the Glass Steagall Act. In 1933 at the height of the depression, Congress passed this law to separate investment and commercial banks. In 1999, President Bill Clinton repealed the law. Today, there are no more independent investment banks on Wall Street. In order to survive, investment banking has to operate under a commercial banking charter. Now for the first time, our government and many governments around the world are involved in every aspect of our financial lives. In the case of the U.S., the federal government either owns or regulates insurance companies, mortgage banks and intermediaries, commercial paper industry, commercial/investment banks, money market mutual funds, and possibly hedge funds as well as the big three automobile companies. During this crisis, many alarms were sounded about the moral hazards that were built into the financial system. With the takeover of private institutions by the federal government, the threat of moral hazard has increased. We the taxpayers have paid for the mistakes of all who have made wrong or inappropriate decisions, and as long as the entire financial industry’s actions are guaranteed by the U.S. government, we will continue to pay for future mistakes. The aggressive intrusion by the government in the free market system ushers in a new era, and if we are not careful, they will remain for a long time and ultimately outlive their original purpose stymieing global and domestic economic prosperity. There will be excessive and counter productive regulations as a response or reaction to the current mortgage-credit-financial crisis. This country and the world are now abandoning the free markets in the time of fear for the protection and safety of their governments. We are willing to give up rights, opportunities and future prosperity for certainty, but if this is sustained, our standard of living and economic opportunity will suffer.

In conclusion, we are in the midst of an unprecedented global financial tsunami. Regulators are scrambling to take control of this morphing crisis. The stock market has responded by wiping out $15 trillion in value and no one knows when confidence will be restored. The real estate market continues its downward spiral, albeit at a slower rate, but the biggest challenge is the looming recession in the U.S. and globally. Central banks will again cut rates in an effort to stimulate spending and borrowing, but, the current economic malaise is not an interest rate challenge. Therefore any further interest cuts will likely have little impact on the real economy. During the next few months it is likely that we will experience cycles of bull markets and the market could regain a fair portion of its recent losses. However, the damage to our financial and economic system has been done, and it will take a long time for it to heal.