- Eight years after the end of the financial crisis, the Global Economy is much healthier and now growing in sync for the first time since 2010. The superb performance in equities/risk assets globally reflects the positive business and consumer sentiments, increased economic activities and more employment.

- The new U.S. tax law passed in December is not popular with those who are deficit hawks or believe that the late stage organic growth of the economy does not require the pro-cyclical fiscal policy. However, its business focused tax cuts and preferences for foreign asset repatriation have given a turbo boost to the economy for 2018, and their positive impact is rippling through the rest of the global economy. IMF credits 50% of the global economic upward revision to the impact from the U.S. tax bill.

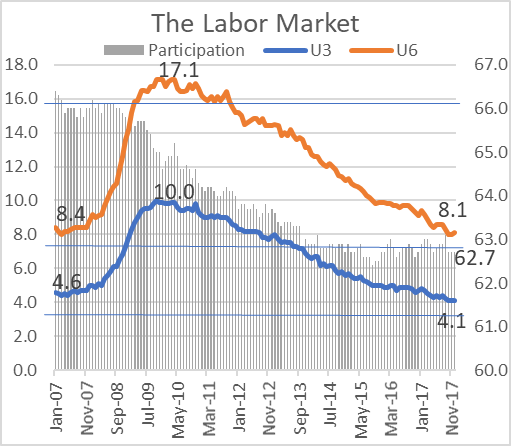

- Unemployment (U3) is at 4.1% and 8.1% for the broader U6 measure and we expect the U3 to be in the mid 3% range by the end of 2018 with a sub 8% U6.

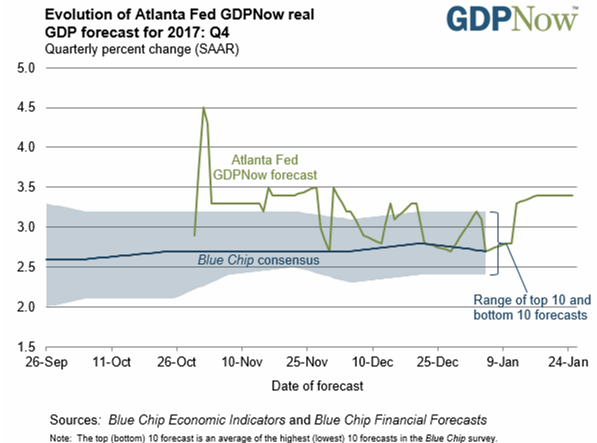

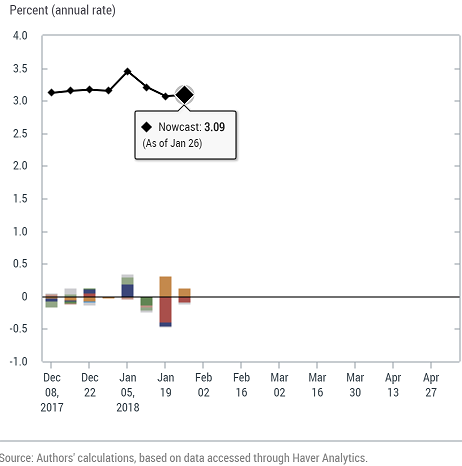

- The advance estimate of 2.6% for 4th quarter GDP came in below the consensus estimate of 2.9%, and 2017 ended at 2.5%, which is at the upper range of the post financial crisis era. With the new tax cut, we expect the GDP for 2018 to be at the 3% level.

- Inflation has been the missing ingredient, and indicators are showing a return. Some of the improvements in inflation may be statistical (i.e. a change in value from a very low starting point), but much will be “pushed” to our economy under a lower US dollar, increased and sustaining energy prices, along with other commodities regime. When wage inflation picks up, inflation will likely be “pulled” as well.

- The 2017 FOMC has been signaling 3-interest rate hikes in 2018. We expect 4-hikes under the new FOMC due to pro-cyclical effects from the new tax bill. Our projection is also due to a possible upside surprise in inflation expectation.

- The likelihood of an inverted yield curve in 2018 has been reduced, and as such, the likelihood of a recession has been pushed out further into 2020 and beyond.

- From an investment standpoint, the seeming parallel universe that we have been traveling in (i.e. risk assets continue to advance despite geopolitical and other systemic risks) will continue, and as such, we are constructive/positive on equities globally. Due to FOMC rate normalization (bad for short end), possible inflation surprises and the less attractiveness of U.S. long yields as other yields begin to move higher, fixed income will likely be delivering a lower to no return in 2018. Commodities have performed well. They typically do at the late stage of an economic cycle.

- Downside risks remain: geopolitical risks from rogue states, findings from the Mueller’s investigation into Russia’s meddling in the 2016 election and the possible Trump campaign’s collusion, and the mid-term 2018 U.S. election outcome, just to name a few.

A New Year

One year ago, we ushered in Donald J. Trump as the 45th President of the United States. Regardless if you supported him or not, all of our predictions or anticipations regarding him and his Administration being unconventional and disruptive came true, in spades. In our 2016 4th quarter review, we stated that “the single word that investment professionals and macro economists can agree on is uncertainty” when thinking about 2017, and we have had plenty of that and a parallel universe between politics and the equity or risk market.

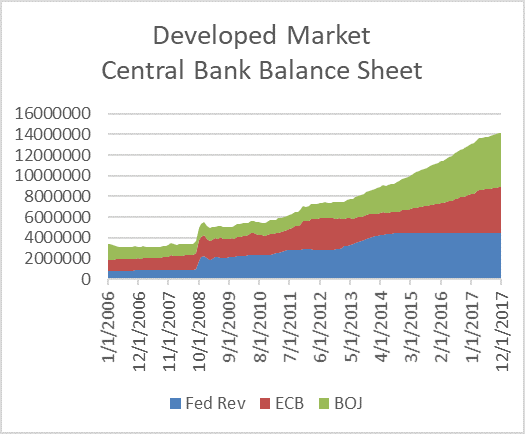

Fast forward 12-months, and we witnessed an all-time-high stock market in the U.S. with muted volatility (as measured by VIX) at the same time the ever-lowering unemployment rate has not yielded the anticipated wage inflation. With the rising stock market and residential real estate prices, the U.S. household wealth reached an all-time-high at $96.9 trillion in the third quarter as reported by the Federal Reserve. Global fear of deflation/disinflation has given way to gradual price stability with inflation in check. Consumer and business sentiments are strong to very strong which have sustained increasing economic activities. The disappearing fear of populism taking over the eurozone that would ultimately lead to the breakup of Europe and the recuperating oil prices that brought Brazil and Russia out of recessions all contributed to a quickening of global economic expansion. Financial conditions have also remained positive with central banks, in the aggregate, continuing their balance sheet expansion. The world remains saturated with liquidity (cash).

Finally, against the backdrop of a strong synchronized economic expansion, in an effort to keep its campaign promise, the Republicans pushed through, along strict party lines, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act which is expected to add $1 trillion or more to the national debt, excluding interest expense. This pro-cyclical fiscal policy is pouring gasoline on a late stage economic cycle here and will have impact globally since we are the largest economy in the world. Much of the tax cut will benefit corporations and the wealthiest tax payers. This is a vote for trickledown economics. Although the new law will likely add 50 to 70bp to the near-term U.S. GDP, this form of deficit spending will limit our ability to apply meaningful fiscal stimulus when the next recession or economic crisis dawns. This is even more troublesome when it is happening at a time when the monetary policy options are very limited after almost a decade of zero bound interest rates and a 500% increase in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

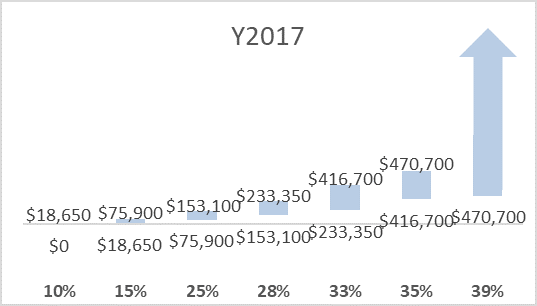

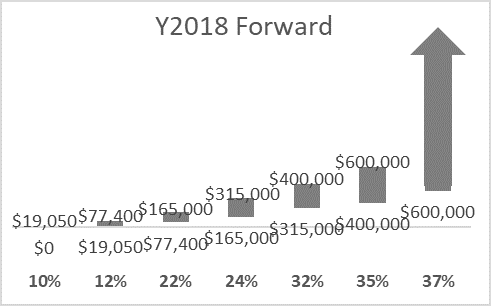

The single biggest event in the fourth quarter was the passage of the new tax bill. In order to pass the Republican Party tax legislation, a special budget reconciliation procedure in the Senate to require a simple majority was used. There are still a number “fixes” that are needed by Congress since the tax bill was rushed through both chambers of Congress. An analysis of the new tax act or its impact over the next 10 years on the economy are beyond the scope of this quarterly review. Overall, the new law has significantly reduced corporate taxes permanently from 35% to 21% with the alternative minimum tax (AMT) repealed and modified the individual tax bracket with sunset provisions in 10 years.

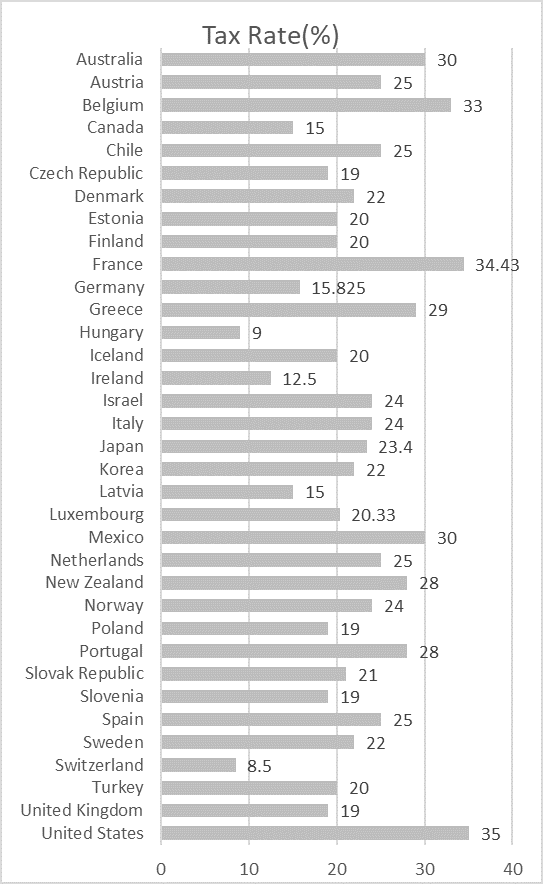

Among the OECD countries[1] (the largest global economies), the U.S. has always been considered the country that imposes the highest statutory corporate federal income tax. With the federal statutory rate of 35% plus an average of the corporate income taxes levied by individual states, the total statutory corporate income tax rate is 38.91%. This would be the 4th highest rate in the world.

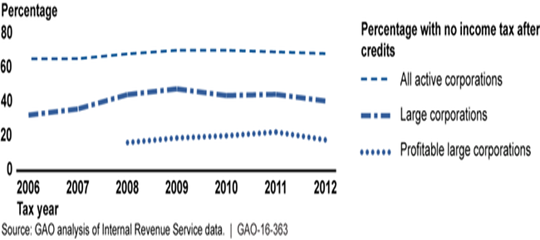

According to GAO’s report[2] that “from 2006 to 2012, at least two-thirds of all active corporations had no federal income tax liability. Larger corporations were more likely to owe tax. Among large corporations (generally those with at least $10 million in assets) less than half – 42.3% – paid no federal income tax in 2012. Of those large corporations whose financial statements reported a profit, 19.5% paid no federal income tax that year.”

Although the highest rate may be the U.S., the net effective rate paid by U.S. corporations is lower to much lower than either 35% or almost 39%. Again, according to the GAO study, “For tax years 2008 to 2012, profitable large U.S. corporations paid, on average, U.S. federal income taxes amounting to about 14% of the pretax net income that they reported in their financial statements (for those entities included in their tax returns). When foreign and state and local income taxes are included, the average corporate effective tax rates across all of those years increases to just over 22%.”

Nonetheless, the lowering of the corporate tax rate will have an overall positive impact on the amount U.S. corporations will be paying in taxes and make America’s tax rate more in line globally.

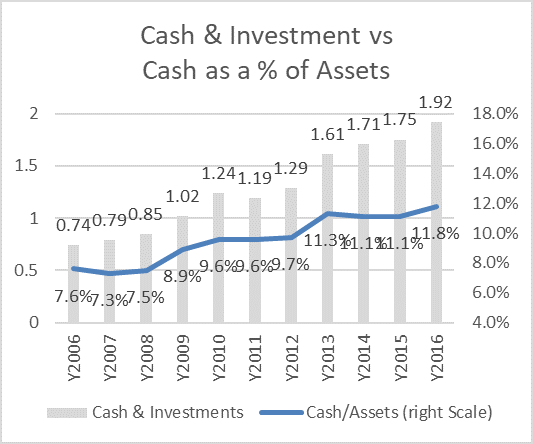

Additionally, the tax law sets a one-time mandatory tax of 8% on illiquid assets and 15.5% on cash and cash equivalents for U.S. business profits now held overseas. This is estimated at $2.6 trillion. According to S&P Global[3], the top 1% of U.S. nonfinancial corporate borrowers holds more than half of the record $1.9 trillion in cash and short- and long-term liquid investments at 2016 year-end. The combination of the repatriation and the existing cash on corporate balance sheet offers company with added business options.

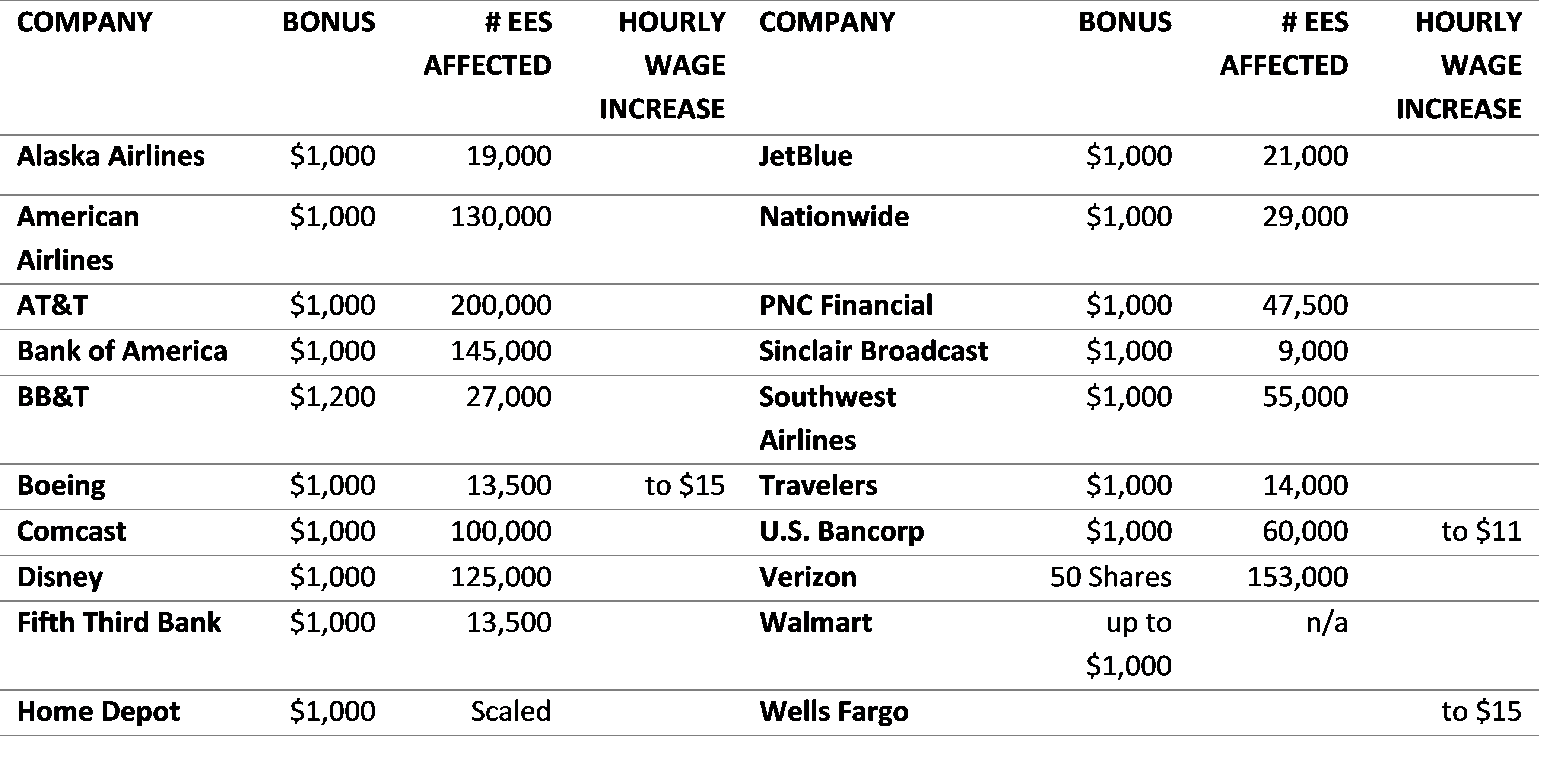

With corporate America flush with cash, it is the hope that the added cash will be deployed to improve productivity, increase research and development and make investments that would produce long term benefits for the corporations, shareholders, and workers, but short-termism may push companies to use a portion of the repatriated assets to be returned to their shareholders in the form of dividends and buy back stocks (getting perhaps increasingly more expensive to do so with a rising equity market) to boost their share prices. We expect more robust merger and acquisition activities to boost revenue and improve synergy. It is too early to know in what direction the majority of companies will deploy the added liquidity. Additionally, many corporations have announced one-time increases and bonuses to their non-executive or management employees[4]. This is short-term stimulus for the economy and improves consumer sentiment.

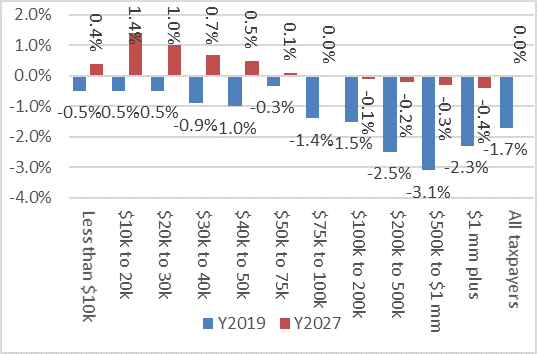

Most of the changes affecting individual taxpayers are scheduled to expire or sunset after December 31, 2025, and to revert to their pre-2018 form. The new tax rates favor the highest income earners.

In an effort to get the tax bill passed through the reconciliation procedure in the Senate, the new reduced tax brackets will reverse themselves in 10-years so that the projected deficit will be within required boundaries. Nonetheless, the graph on the left (provided by Goldman Sachs) shows that the lowered tax rates are tilted in favor of the highest income taxpayers now, and when the tax rates revert, the same graph is projected to remain favoring the same high income group.

Global Synchrony

As the world economic, political and business leaders meet at Davos this week for the World Economic Forum, the IMF has updated its economic forecast, and it is really good. For 2017, global output is estimated to have grown by 3.7%, which is 0.1% faster than expected since the fall and 0.5% faster than originally projected in 2016. The growth has been broadly participated in globally with upside surprises coming from Europe and Asia.

With (1) geopolitical risks that threatened the breakup of the eurozone union and single currency subsiding (extreme populism and eurosceptics are not in power; Brexit is a slower moving train than anticipated with Northern Ireland and Scotland remaining in the UK; and Catalonia failed to become an independent state), (2) the recovery in energy prices that helped push Brazil and Russia out of their recessions, (3) a continuing expansion of the Chinese economy without any sign of a hard landing, and, last but not least, (4) a super supportive global central bank liquidity, global consumers and businesses turn from caution to optimism.

Global central banks remain accommodative with mostly low to very low interest rates. At the same time, the total balance sheets of the three major central banks continue to expand on an aggregate basis (even though the Federal Reserve last year began to “normalize” its balance sheet).

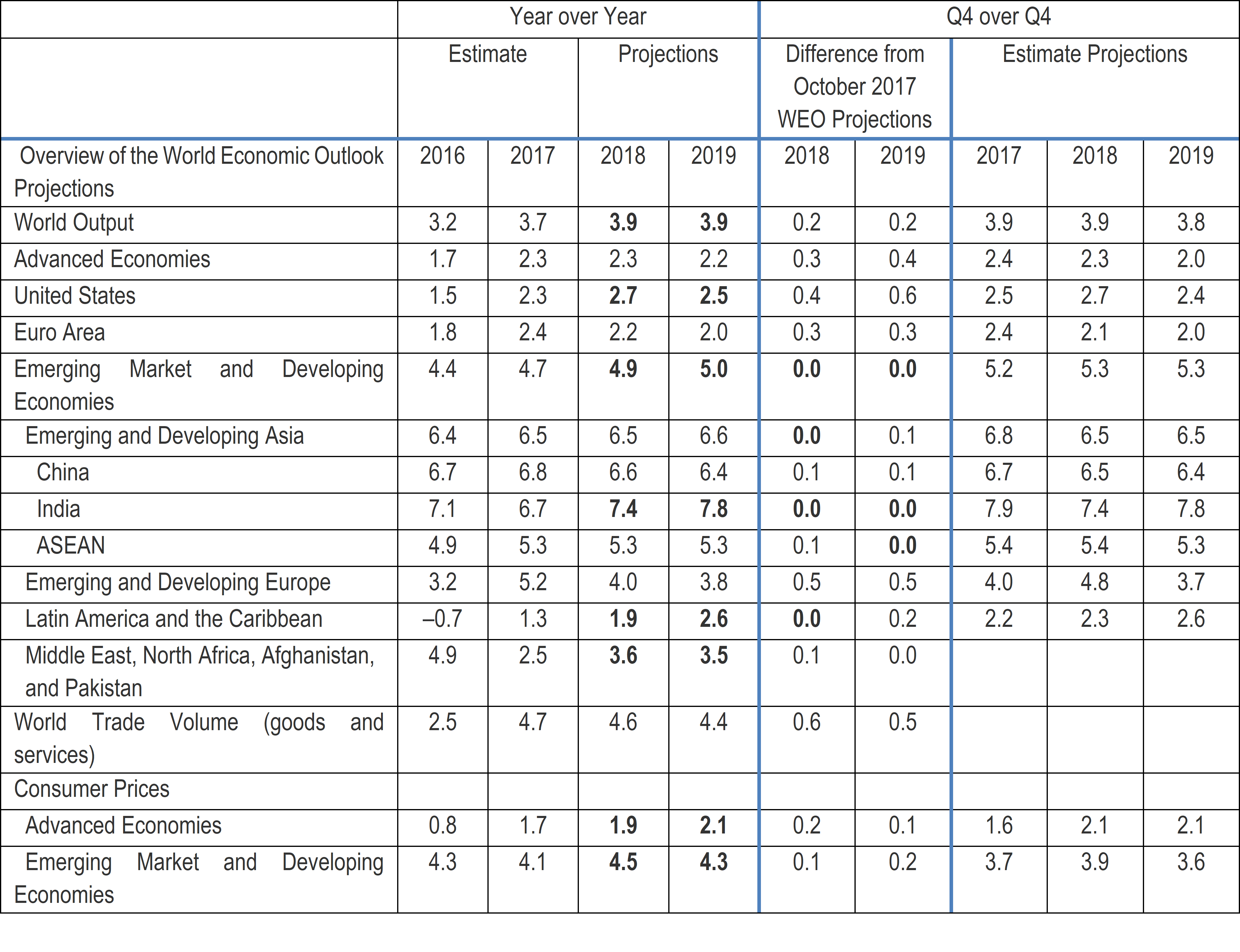

The IMF makes the following observations and forecasts:

- Global economic activity continues to firm up with broad pickup in growth, especially in Europe and Asia. This is the broadest synchronized global growth upsurge since 2010.

- Global growth for 2017 is now estimated at 3.7%, 0.1% higher than projected in the fall. The stronger momentum experienced in 2017 is expected to carry into 2018 and 2019, with global growth revised up to 3.9% for both years (0.2% higher relative to the fall forecasts).

- For the two-year forecast horizon, the upward revisions to the global outlook result mainly from advanced economies, where growth is now expected to exceed 2% in 2018 and 2019. This forecast reflects the expectation that favorable global financial conditions and strong sentiment will help maintain the recent acceleration in demand, especially in investment, with a noticeable impact on growth in economies with large exports.

- The U.S. tax policy changes are expected to stimulate activity, with the short-term impact in the United States mostly driven by the investment response to the corporate income tax cuts. The effects of the tax package on output in the U.S. and its trading partners contribute about half of the cumulative revision upward to global growth over 2018–19.

- In the near term, the global economy is likely to maintain its momentum absent a correction in financial markets—which have seen a sustained run-up in asset prices and very low volatility, seemingly unperturbed by policy or political uncertainty in recent months. Such momentum could even surprise on the upside in the near term if confidence in the global outlook and easy financial conditions continue to reinforce each other.

- Over the medium term, a potential buildup of vulnerabilities (if financial conditions remain easy), the possible adoption of inward-looking policies, and noneconomic factors pose notable downside risks.

The table above is the summary of projections from IMF for the global economy. Without exception, IMF has not revised down projections (4 regions or countries are flat) from its October 2017 projections. Inflation globally has been marked up but is seemingly within control. The most significant revision is the improvement in economic activities in the U.S. with an upward revision of 0.4% in 2018 to 2.7% and a 0.6% revision to 2.5% in 2019.

Depending on business and consumer sentiment, the signs of wage inflation, the handoff from monetary policy (i.e. the speed of rate normalization and if balance sheet normalization path would be altered) to fiscal policy and the private economy, and the absence of internal and external political hiccups, the U.S. economy could further surprise on the upside in 2018.

The U.S. Economy – Real GDP

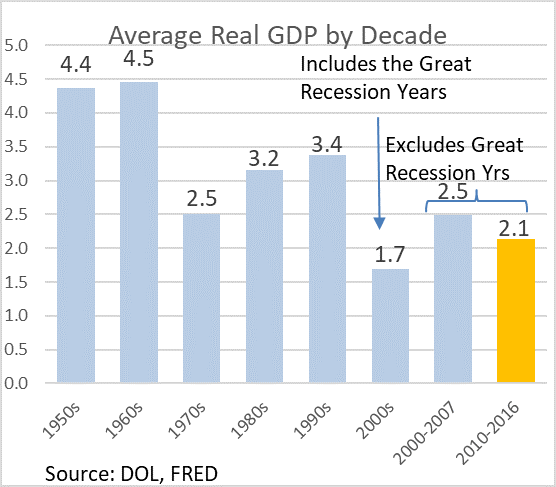

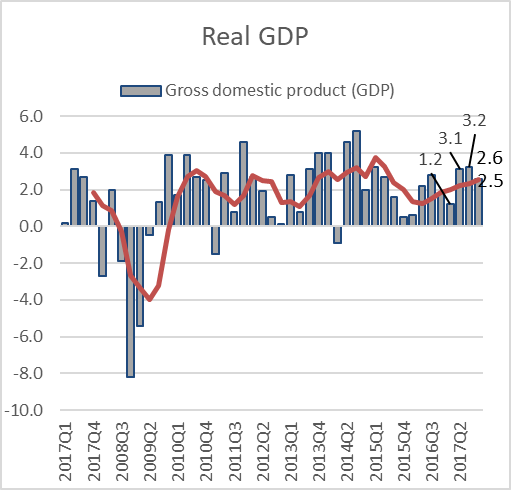

With the advance estimate for the 4th quarter came in at 2.6%, the real GDP for the full year of 2017 is now at 2.5% and in line with the average GDP from 2000 to 2007. The 4th quarter GDP is lower than the consensus estimate of 2.9%. The advance estimate is based on incomplete data and second and third revisions will provide a more complete picture. It is possible that the final GDP to be higher than 2.6% and closer to the 2,9%.

Historically, the average real GDP for the U.S. has been 3.6% including the super growth years in the 50s and 60s. However, for the first decade in the 21st Century, after the burst of the Tech Bubble and including the mortgage meltdown led Global Financial Crisis, the average GDP was only 1.7%. From 2010 through 2016, the U.S. GDP has been at an average of 2.1%, even lower than the decade of the 70s.

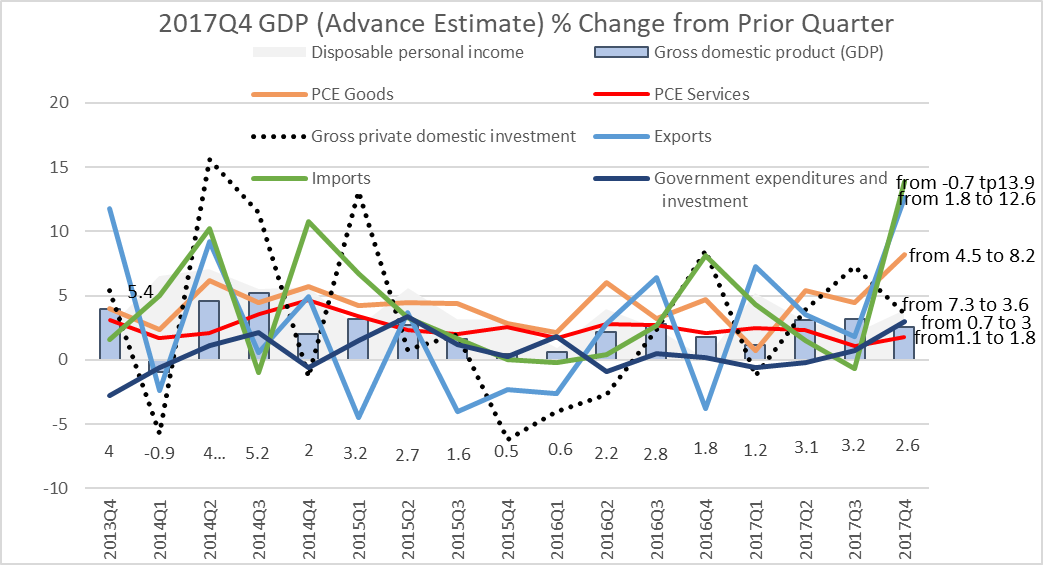

Since the trailing 4-quarter low reached in the second quarter of 2016, the real GDP has been steadily moving higher to the current 2.5% annual pace. According to the advance estimate, the largest contributors to the U.S. economy during the fourth quarter as compared to the third quarter are personal consumption expenditures (PCE) in goods, nonresidential fixed investment or private capital expenditure, and exports (even though imports have jumped, which is a detractor).

Going forward, we are cautious about the consumer (unless real wage growth turns solidly upwards) as debt increases and savings decreases.

The private sector economic growth handoff from here may well be moving from the expansion of consumer spending to capital expenditure (capex), which is robust (and we expect this to turn even higher) along with more government spending. Further, with a weaker dollar, exports should continue to do well. Atlanta Federal Reserve continues to predict that the fourth quarter will be revised up from 2.6% to 3.4% (we are doubtful) while the New York Federal Reserve’s Nowcast is predicting (at this very early stage) that the first quarter real GDP is growing at 3.09%.

The Labor Economy

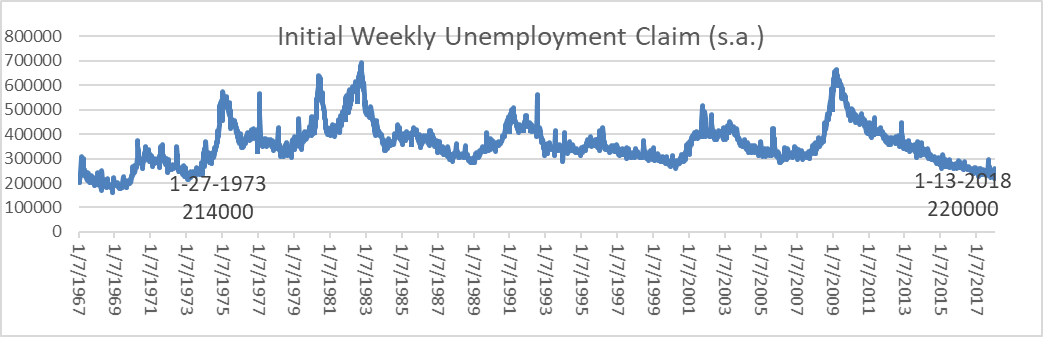

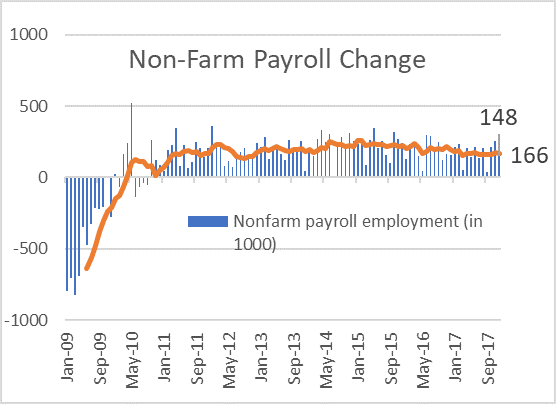

According to the latest Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims News Release on January 18, 2018[5], for the week ending January 13, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 220,000, a decrease of 41,000 from the previous week’s unrevised level of 261,000. This is the lowest level for initial claims since February 24, 1973, when it was 218,000.

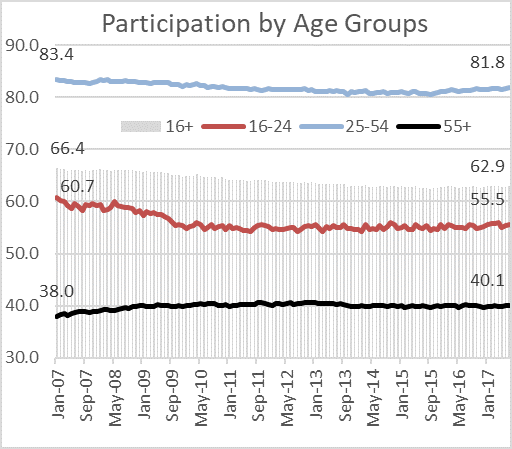

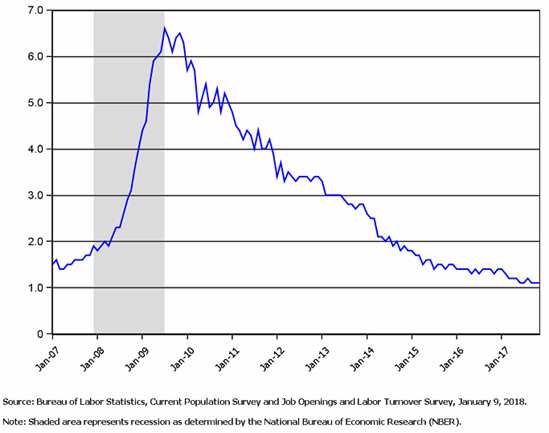

As of the end of 2017, the unemployment rate (U3) remained at 4.1% for the third month and is now over 0.5% below the pre-Great Recession level of 4.6% set in January 2007. The broader unemployment measure that includes discouraged, marginally attached workers and those who are part-time purely for economic reasons is now at 8% which is below the 8.4% level in January 2007, but the participation level has not improved and remains at 62.7% for the third month. This stubbornness has more to do with demographic changes and other factors. The Participation by Age Group[6] data clearly shows that the participation rate for the age 16+ population as a whole at 62.9% remains below the January 2007 level of 66.4%. This is also true for the age groups of 16 to 24 and 15 to 54, but for the 55+ age group, the 40.1% participation rate is now higher than the 38% in January 2007. In fact, the older the age group, the greater the participation rate improvement. This means a segment of the Baby Boomers is either unable or unwilling to retire and remains in the workforce.

The table above shows the percentage of population employed based on age group. It suggests that there may still be some slack in the labor force. In an attempt to explain the stubborn low labor participation rate, in 2016 Alan Krueger of Princeton published his paper “Where Have All the Workers Gone?”. He found that “nearly half of prime age not in the labor force men take pain medication on a daily basis, and in nearly two-thirds of those cases, they take prescription pain medication.” In his Fall 2017 follow-up paper[7], Krueger concluded that the increase in opioid prescriptions from 1999 to 2015 could account for about 20% of the observed decline in men’s labor force participation, and 25% of the observed decline in women’s labor force participation. Even though much of the labor participation “rate decline can be attributed to an aging population and other trends that pre-date the Great Recession (for example, increased school enrollment of younger workers), an increase in opioid prescription rates might also play an important role in the decline, and undoubtedly compounds the problem as many people who are out of the labor force find it difficult to return to work because of reliance on pain medication.” If Krueger’s conclusion is correct, then we are closer to full employment now.

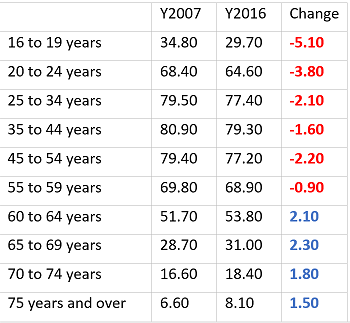

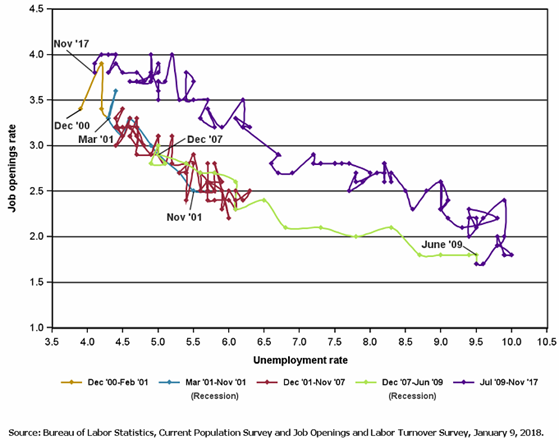

In this graph, the Beveridge Curve plots the job openings rate against the unemployment rate. The economy’s position on the downward sloping Beveridge Curve reflects the state of the business cycle. During an expansion, the unemployment rate is low and the job openings rate is high. Conversely, during a

contraction, the unemployment rate is high and the job openings rate is low. A greater mismatch between available jobs and the unemployed in terms of skills or location would cause the curve to shift outward (up and toward the right). From the start of the most recent recession in December 2007 through the end of 2009, the series trended lower and further to the right as the job openings rate declined and the unemployment rate rose. In November 2017, the unemployment rate was 4.1% and the job openings rate was 3.8%.

According to the latest BLS report[9], the ratio between job openings and job seekers is 1.1. That means, on average, there are as many jobs available as those looking to find one. Of course, skill and job mismatch are not taken into consideration here. Putting this into context, BLS states that “When the most recent recession began (December 2007), the ratio of unemployed persons per job opening was 1.9. The ratio peaked at 6.6 unemployed persons per job opening in July 2009 and trended downward until the end of 2015 and again in 2017.”

We expect the U3 unemployment to continue to grind lower in 2018. In the case of NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), we are most likely there even though the unemployment rate would likely be lowered into the upper 3% range this year as the missing wage inflation returns.

The Mighty Consumer

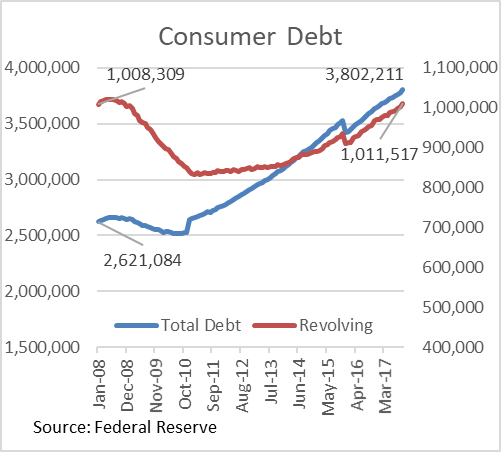

After 9 years since the end of the Great Recession, on average, the consumer seems to be feeling better and consuming more, borrowing more and saving less. The ever-lowering unemployment rate and the new financial and real estate wealth created have given consumers more confidence. As a consequence, total consumer debt has surpassed the January 2008 level, and revolving debt is now back to the same January 2008 level.

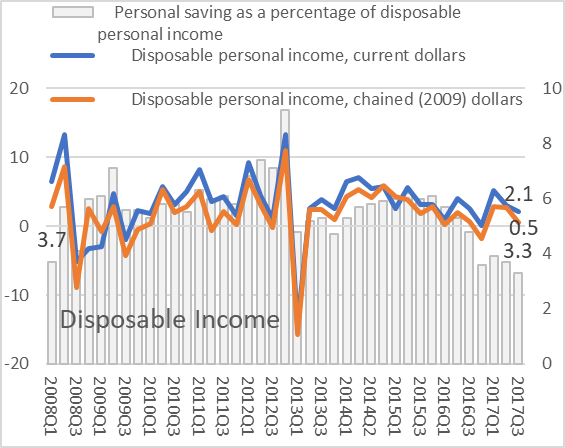

With disposable income increasing at 2.1% in Q4 from the prior quarter (or 0.5% in real terms), savings, as a percentage of disposable personal income, continues to decline from 3.9% and 3.7% in Q2 and Q3 respectively to Q4 at 3.3%. Consumers are saving at an even lower level than the pre-crisis level of 3.7% in 2008 Q1. Consumers have been financing their spending by saving less and now borrowing more. Any future expansion in spending will be fueled by more borrowing unless we see higher wages. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit[10] for the third quarter, there is an increase in delinquency for auto loan and credit card debt.

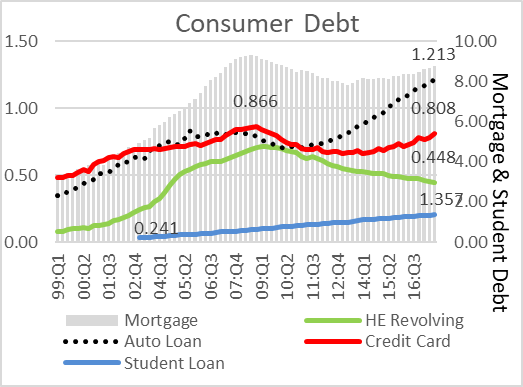

The above graph shows the significant increase in auto loans and the slowly increasing credit debt to the pre-crisis level of $0.866 trillion. The other obvious sign is the continuing increase in student loan debt, now at $1.357 trillion. What is also interesting is that, with total home prices exceeding the pre-crisis high, the total home mortgage is now at $8.69 trillion when compared to $9.29 trillion high reached in 2008 Q3. Home equity (HE) loan is now at $0.448 trillion compared to the high of $0.74 trillion in 2009 Q4.

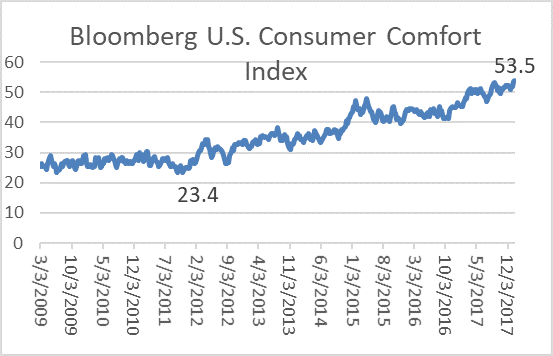

In the meantime, it is not surprising that the Bloomberg Consumer Confidence Index, which measures views on the condition of the U.S. economy, personal finances and the buying climate, is at a 17 year high.

According to S&P DowJones[11], the CoreLogic Case Shiller Index continues to move higher. If there is a 5% rise in the Index in 2018, then we expect an additional $1 trillion in home-equity wealth created.

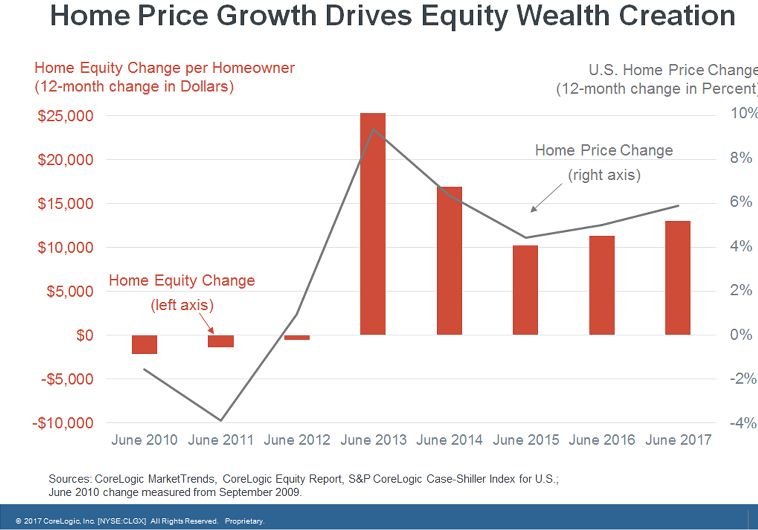

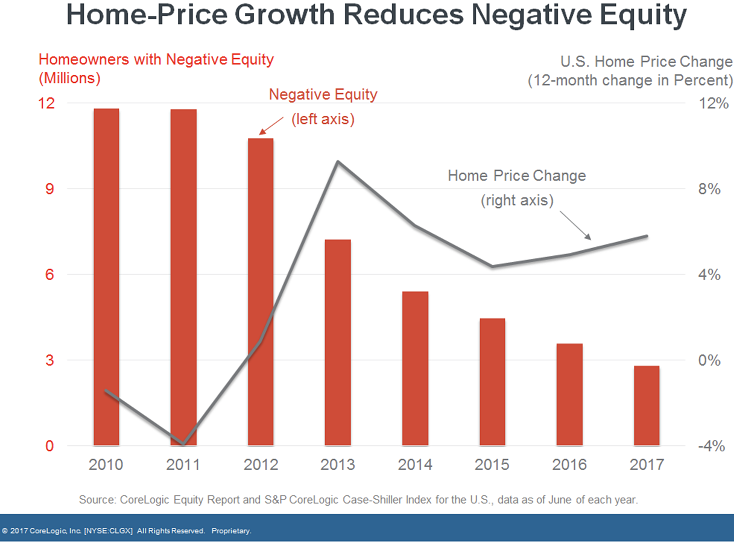

“The latest flow-of-funds data from the Federal Reserve confirmed that home-equity wealth reached a new nominal high this year: $13.9 trillion at mid-2017, $0.5 trillion above the 2006 peak and more than double the $6.0 trillion amount at the trough of the Great Recession.

While several factors will affect aggregate home equity, it’s clear that much of the recovery in home-equity wealth is due to the rebound in home values: The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Index for the U.S. was up 40% (seasonally adjusted) through June from its February 2012 nadir. Comparing annual home-price growth with the annual change in home equity per homeowner shows a strong correlation. When prices are stagnant of falling, equity typically declines. Conversely, price growth generally supports equity accumulation, with faster appreciation leading to larger amounts of equity creation. Home-equity wealth is an important component of family savings, accounting for about 20% of homeowners’ net worth, on average[12].”

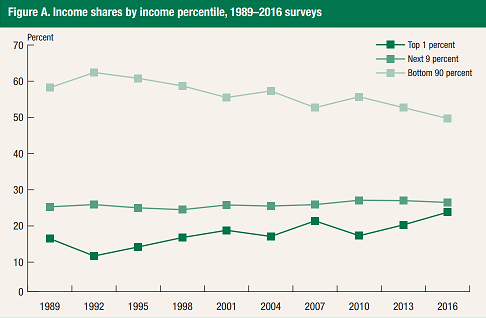

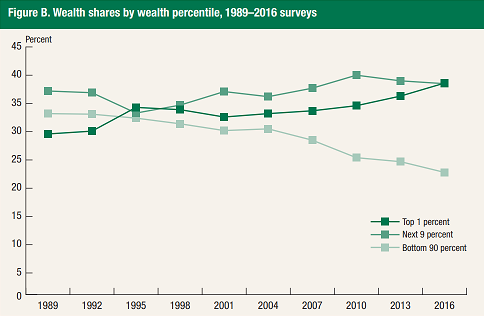

According to the same Federal Reserve, the wealth share of the top 1% (figure A) climbed from 36.3% in 2013 to 38.6% in 2016, slightly surpassing the wealth share of the next highest 9% of families combined (figure B). After rising over the second half of the 1990s and most of the 2000s, the wealth share of the next highest 9% of families has been falling since 2010, reaching 38.5% in 2016. Similar to the situation with income, the wealth share of the bottom 90% of families has been falling over most of the past 25 years, dropping from 33.2% in 1989 to 22.8% in 2016.

These trends are very difficult to reverse, and with the new tax cuts, it is further rewarding the top income and wealth groups in hopes of “trickle down” economics to work. The possible silver lining is for corporate America to use the tax savings to ultimately expand and improve the income of the average worker.

The Long-Awaited Inflation

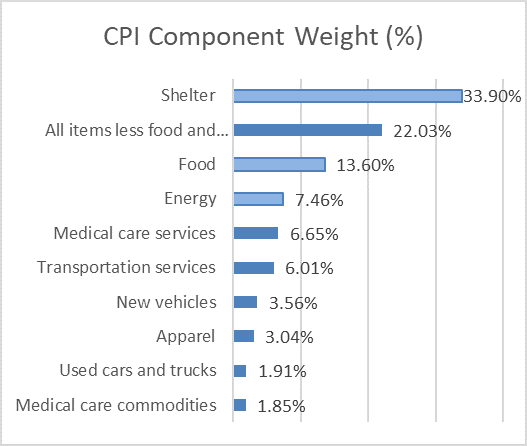

The cost of shelter has the highest price allocation in the current CPI basket at 33.9%. The combination of shelter, food, medical care, transportation and energy (commodities and services) represent almost 68% of the entire consumer basket. The December CPI release shows that shelter component was up 0.4% from November and medical services was up 1%.

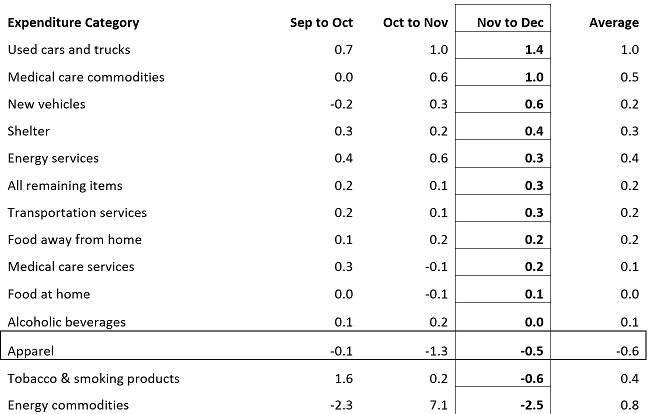

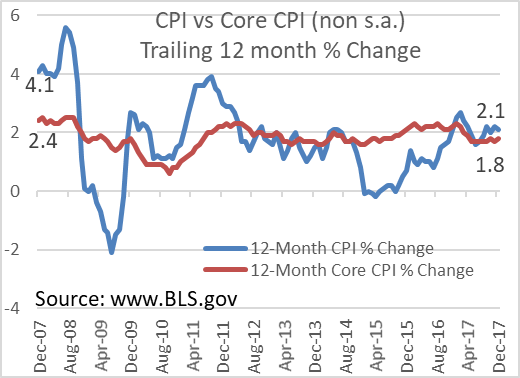

The CPI was up 2.1% (non-seasonally adjusted) for the year and up 0.1% (seasonally adjusted) for the month from November.

The core CPI (CPI excluding volatile components of food and energy) was up 1.8% for the year (non-seasonally adjusted) and up 0.3% (seasonally adjusted) for the month from November. This is the largest monthly change since January 2017 with all categories showing increases with the exception of appeal and tobacco & smoking products.

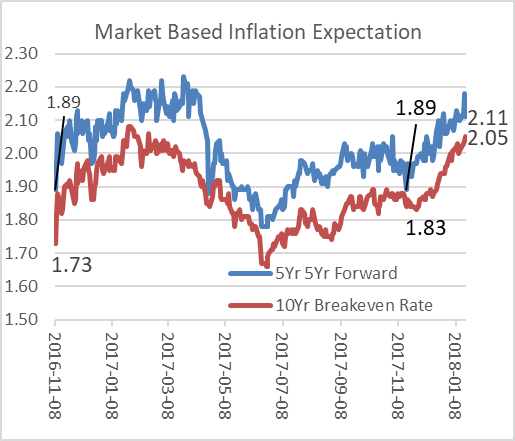

Inflation is much more about expectation,[13] and there are two ways to assess public sentiment. First is the market based (professional) measure. The 5-Year, 5-Year Forward measures the expected inflation (on average) over the 5-year period that begins 5 years from today (i.e. the amount of carry or compensation needed to take on the inflation risk). The indicator has risen from 1.89% in June to 2.11% on January 18th. The 10-Year Breakeven Inflation Rate represents a measure of expected inflation derived from 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Securities. This has moved from 1.83% in June to 2.05 on January 18th.

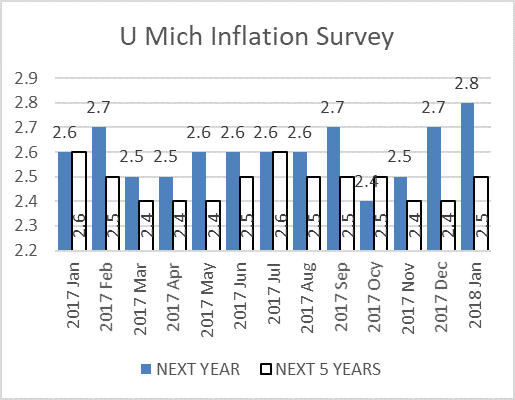

The second way is survey based measures. The most well-known survey is the University of Michigan’s monthly survey of inflation expectation[14]. In its latest survey of inflation expectation for next year, we witness an increase from 2.4% to 2.8% over three months. In the meantime, the expectation for inflation over 5-years remains fairly constant rising only slightly from 2.4% to 2.5%. This means consumers are expecting an acceleration in inflation this coming year but less so in the longer term. This appears consistent with the long term disinflation trend due to technology advancement and demographics.

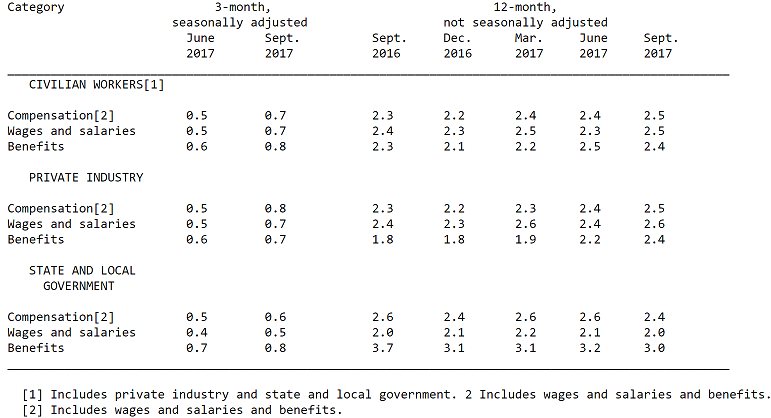

According to BLS release of Employment Cost Index Summary[15], as of October 31, 2017, the seasonally adjusted compensation cost for civilian workers increased 0.7% for the third quarter and 2.5% for the trailing 1-year period.

Although most observers have suggested that there is no wage inflation but if we take benefits (which is a part of total compensation) into consideration, a trailing 12-momnth 2.5% increase is above the 2% CPI or 1.5% PCE. The more encouraging sign is the gradual/slow increase in total compensation from quarter to quarter in 2017 as well as from 2016 to 2017.

Interest Rates

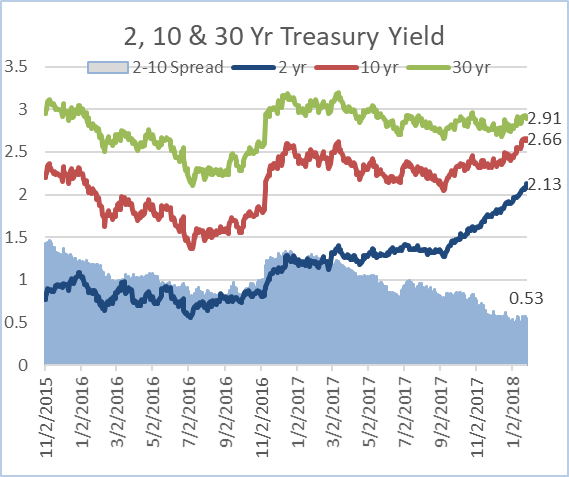

The two-year treasury has steadily been moving higher from 0.77% on Nov 2, 2016, to 2.13% on January 26, 2018. The two-year is often considered the benchmark for the risk-free rate and is directly impacted by the FOMC rate actions. The left graph shows the movement of the 2-, 10- and 30-year treasuries over the time series, and two things are most notable: 1) the rise of the 2-year and 2) the narrowing of the interest rate spread between the 2- and the 10-year securities. Currently, the yield difference between the two is 53bp (or 0.53%) as compared to 1.43 at beginning of the time series. Clearly interest rates across all three treasury maturities have risen, but the rate of change has been most significant for the 2-year. There are many factors that contribute to a more stable 10-year (safe haven securities, rate arbitrage by foreign buyers, etc.) and 30-year (lack of meaningful inflation, non-economic buyers, etc.) since the financial crisis. The fear has been the flattening of the yield curve will lead to an inverse yield curve where the short end is yielding a higher rate than the back end. This has traditionally lead to a recession within 6 to 9 months. However, the 10-year yield has picked up lately.

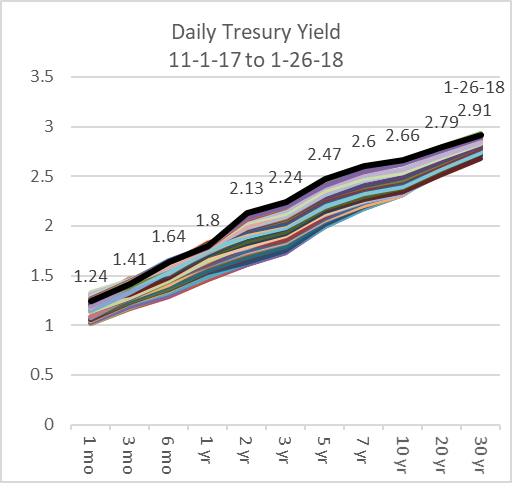

The left graph shows the daily yield curve since November 1, 2017 through January 26, 2018. The thick black line floating at the top end of the band is the current yield curve. This means that the entire yield curve has moved up (i.e. higher rates along the entire yield curve). The 10-year is now 2.66% as compared to a 2.05% yield just less than 4-months ago. We believe that, with the economy picking up steam and the likelihood of inflation reaching and even passing the target 2%, the yield curve will continue to move up. If the FOMC raises rates faster and with more frequency, the yield curve could flatten some more, but we expect the 10-year to move higher from here as well.

What is in store for 2018?

In conclusion, we are much more positive about 2018 than 6 months ago. We see more upside to the US and world economy than downside this year with strong momentum (rate of change) which will likely lead to upside surprise. Since many of the 2016 and 2017 downside risks have vanished or not been realized and the $1.5 billion of deficit driven fiscal stimulus from the U.S. tax cut, the long US economic cycle is now further extended. This is happening at a time when the world central banks remain accommodative in rates as well as continuing balance sheet expansion. We are fanning the fire of economic activities.

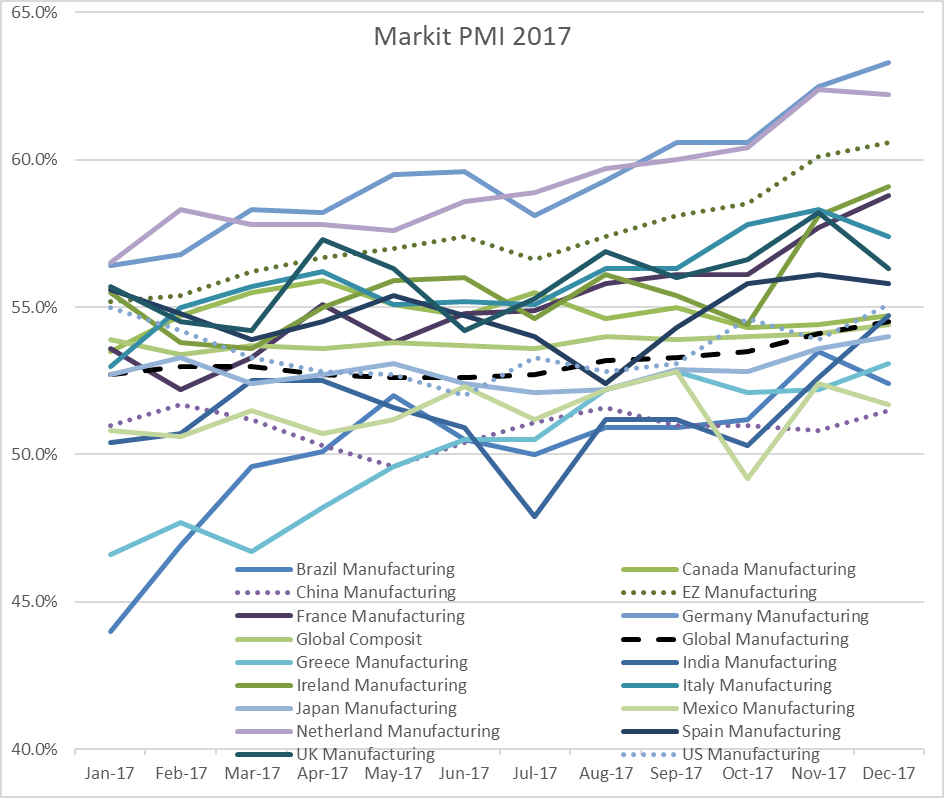

The excitement is not contained in the U.S. alone. Regardless of President Trump’s seemingly anti-globalization, anti-multilateral trade and anti-global/international organization rhetoric, world trade has been on the rise and globalization around the world continues unabated[16]. The dependency among developed, developing, emerging and frontier markets remains. The recovery in developed economies growth helped to spark the growth of export driven (commodities and manufacturing) emerging and developing economies. The following graph shows the Markit PMI survey of most of the largest world manufacturing economies, and the trend is clearly up during 2017 and continuing into 2018.

However, this is likely to be cyclical, and long-term challenges and structural obstacles have not disappeared.

It is without dispute that the stock market has had a great run in 2017 and the valuation is quite stretched, but when comparing equities to fixed income at this point of the economic cycle, and in light of the positive momentum and sentiment, equities is favored. Assuming cash is not a viable investment asset (since it is producing negative real rate of return), then fixed income is the natural alternative for safe assets. With short term interest rates on the rise (due to FOMC action), the short yield of the yield curve is not a place to look for return (even though as rates rise short dated bonds may lose money but also quicker in reinvesting into higher yielding securities to make up the losses). Long end of the yield curve is often considered the proxy for inflation. If we expect there is a real risk for upside surprise, the long-dated bonds are not a safe place to seek return. As such, the belly (5-7 years) of the yield curve remains the “best among the worse” segments of the fixed income to seek shelter. When invested in the highest quality bonds (i.e. take on no and little credit risk), it serves more as a defensive strategy against any risk-off events in equities rather than a good source of income.

Broadly speaking, U.S. equities remain attractive, but equities in developed economies of Europe and Japan are also attractive especially if we believe that U.S. dollar is not likely to gain strength. Certain emerging and developing market equities are also attractive as well as certain local market (non-hard currency) bonds. The world’s synchronized economic growth is powerful and is not likely to slow down in the near term. This provides investment opportunities. These are general comments. All such investments in risk assets carry downside risks, and depending on the investment time horizon and objectives, one can lose investment principal.

Going forward, the three largest investment risks are disappointing earnings, monetary policy overreach by central banks and geopolitical events (including the outcome of the Mueller investigation of Russia meddling in the U.S. 2016 election and the possible obstruction of justice by President Trump as well as the U.S. mid-term election results).

We are more optimistic about the short-term U.S. economy than six months ago, and we do not expect an economic slowdown or recession in the foreseeable future. We do not expect to see an inverse U.S. yield curve but rather increasing yields across the yield curve and with a return of a small amount of term premium (i.e. the yield curve to be a little less flat). We look forward to learning about the new FOMC Chairman Powell.

Sincerely yours,

CHAO & COMPANY, LTD.

Philip Chao

Principal & CIO

This quarterly commentary represents the current views of Chao & Company, and they are subject to change. This Firm has no obligation or responsibility to update our views. The comments and views should not be deemed as Philip Chao, or any member of this Firm, offering personal or personalized investment advice. The quarterly commentary is informational only and is insufficient to be relied upon to make any financial or investment decisions or to make any changes to your financial condition.

[1] http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLE_II1

[2] https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/675844.pdf

[3] https://www.spglobal.com/our-insights/US-Corporate-Cash-Reaches-19-Trillion-But-Rising-Debt-and-Tax-Reform-Pose-Risk.html

[5] https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf

[6] Source: BLS, July 2017 – https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2017/employment-population-ratio-and-labor-force-participation-rate-by-age.htm

[7] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brookings-now/2017/09/07/how-the-opioid-epidemic-has-affected-the-u-s-labor-force-county-by-county/

[8] https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/ceshighlights.pdf

[9] https://www.bls.gov/web/jolts/jlt_labstatgraphs.pdf

[10] https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/news/research/2017/rp171114

[11] http://www.housingviews.com/2017/11/13/home-equity-wealth-at-new-high/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+HousingViews+%28HousingViews+-+S%26P%27s+Blog+on+the+Housing+Market%29

[12]https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf17.pdf

[13] https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/april-2016/inflation-expectations-are-important-to-central-bankers-too

[14] http://www.sca.isr.umich.edu/charts.html

[15] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/eci.nr0.htm

[16] https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2017_e/WTO_Chapter_02_e.pdf